When Edward was captured at the battle of Lewes in May 1264, his ally Prince Dafydd of Wales led an army of Marchers to defend Chester on the prince's behalf. They were roundly beaten in November by Ferrers, who raised an army to invade and seize the lordship for himself. Round One had gone to Ferrers, but he went down in Round Two to a sucker-punch from Simon, who lured the earl to London on inflated charges of treason and then threw him in the Tower.

Round Three, played out at Evesham, was not so much a knockout as a wipe-out. Whether or not Edward meant to kill his godfather – at least one contemporary chronicler says otherwise – Simon ended up being exploded over a wide area. His head and testicles served as table decorations at Wigmore, one foot became the focus of a cult in Northumbria, another foot was sent as a gift to Prince Llywelyn of Wales, while one of his severed hands allegedly had the power to levitate during Mass. I forget what happened to the other.

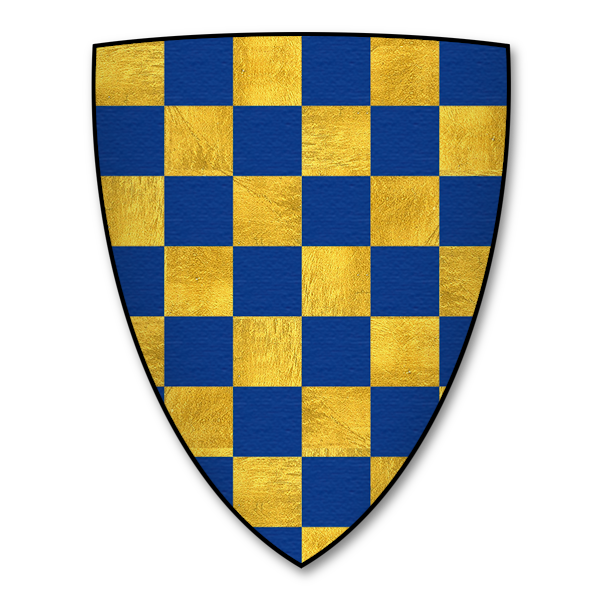

While at Chester, Edward was also concerned with wider affairs beyond the earldom. On 24 August he sent a letter asking the keepers of the royal wardrobe to see that Earl Warenne was empowered to receive the submission of the Cinque Ports. Warenne, sometimes portrayed as a nincompoop thanks to his defeat at Stirling Bridge in 1297, was in reality a brutally effective government enforcer. Anyone can lose a battle.

Edward also asked that letters be drafted inviting the Montfortian garrison at Kenilworth to surrender. They refused and would hold out until December 1266.

Interestingly, the heir to the throne also promised four men that they would continue to hold their lands freely. These were John and Richard Havering, William Turevile and Semanus de Stoke.

Why Edward should have favoured these men in particular is unclear, but the order may imply he knew what was coming next. Disinheritance on a massive scale.

No comments:

Post a Comment