|

| The Treaty of Gwerneigron |

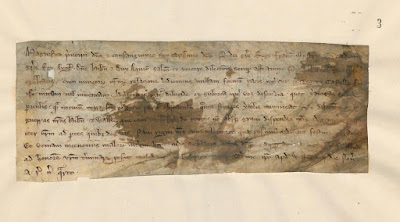

Dafydd undertook to release his brother, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, and to submit to the decision of the king’s court on the share of his father’s lands which Gruffydd ought to have. The king would decide if the case should be settled via Welsh custom or the rule of ‘feudal’ law. Dafydd also agreed that his lands in Gwynedd should be held in chief of the crown, and he surrendered Mold castle and all lands of Henry’s barons and vassals occupied by Llywelyn the Great since the days of King John. He promised to pay war damages and restore the homages which Welshmen had once owed to John, including Welsh nobles.

At London, in October, Dafydd was obliged to go further. He had no direct heir, so Henry induced him to accept feudal law, whereby his land would escheat to the crown upon death. The document states that Dafydd did this of his own free will - "donacione inter vivos" - though we may entertain reasonable suspicions. He also surrendered the manor of Ellesmere, the Welsh cantref of Tegeingl, and the castle and lands of Degannwy.

Gruffydd, that unhappy man, had been well and truly set aside. Henry kept him in the Tower of London, to use as potential leverage against his brother. His active career was over.

He still had a theoretical purpose. Henry, an underrated politician, had declared his intention to partition Gwynedd between the brothers. In reality he wished to establish a principle: the king sought to reverse the unity sought by princes of Gwynedd ever since the days of Gruffydd ap Cynan, and he used the Welsh law of partible inheritance to do it. This meant he could use the ‘custom of Wales’ against any Welsh prince, as the princes themselves were all too aware. In a bid to keep their territories intact, they rushed to make peace with the king.

For the moment, Dafydd was left politically isolated. He would remain so as long as Gruffydd was alive.