Naturally, all this aggressive expansionism met with resistance. Edward failed in Scotland but succeeded in Wales; Philip failed in Gascony and imposed a sort of half-conquest on Flanders; Adolf failed in all respects and was chopped up on a German battlefield. His dismal fate was shared by the likes of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, whose efforts to establish a united Wales ended in disaster, and the Count of Holland, flung into a ditch and stabbed to death by his own nobles.

Other than crude power-grabbing, what was the ideology beyond the expansion of medieval states? One might say it was the logical effort to bind together a single people with their own laws, language and culture. That’s a little too pat, and doesn’t explain why Llywelyn, Adolf and Count Floris (among others) were abandoned at crucial times by their own people.

|

| Philip le Bel |

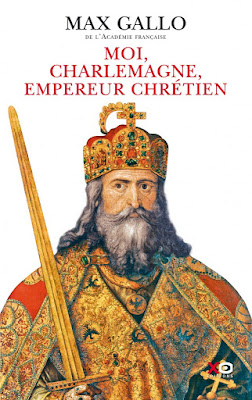

One aspect was the ‘religion of monarchy’. Philip le Bel was the greatest exponent of this: he was the most powerful monarch in Europe, the Vicar of God, the chief pillar of the Church, the inheritor of the holy insignia and unifying mission of Charlemagne. To oppose him was not only evil, it was sacrilegious. In his mind, and that of his fanatical chancellor Pierre Flote, there was no conflict. As Guillaume de Nogaret, another of Philip’s ministers, succinctly expressed it:

‘No true believer can fail to see that the interests of the French monarchy and the interests of the Church are identical. The Flemings are heretics, and Pope Boniface is a heretic, because they oppose the King of France, who is the pillar of the Church’.

The third pic is of the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, a terrific bit of bling.

No comments:

Post a Comment