The Dragon of Chirk (2)

On 12 April 1277 Madog ap Gruffudd, eldest son of Gruffudd of Bromfield, defected to the king of England. His brother Llywelyn Fychan had done so back in December 1276, and now he followed suit. Madog was pressured into this decision by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and William Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who marched an army down from Chester into Powys Fadog.

Professor J Beverly-Smith states that Dafydd and his English ally ‘tore apart’ the unity of northern Powys. This is a rare mistake by Prof B-Smith, since the lordship had already been divided by Prince Llywelyn in 1270.

The terms of Madog’s submission hint at pre-existing internal divisions inside Powys. Madog was not to reproach or harm those of his tenants who had already gone over to the king. He would in future hold his lands as a tenant-in-chief of the crown, just as his brother Llywelyn had agreed to separate his lands from the principality of Wales. It was further provided that if Prince Llywelyn drove Madog from his lands, the king was obliged to find houses for Madog and his men to live in.

This agreement undermined Prince Llywelyn’s efforts to take direct control of Powys Fadog at the start of the war. In 1278 Madog’s mother, Emma Audley, claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her lands of Overton and Maelor Saesneg “in time of war” and given them to Madog. Llywelyn’s sister Margaret claimed that Llywelyn had invaded her land in Glyndyfrdwy and given it to Gruffydd Fychan, one of Madog’s brothers.

In summary: the Prince of Wales took his sister’s land and gave it to her brother-in-law and took his sister’s mother-in-law’s land and gave it to her son who was also his sister’s brother-in-law and then the two brothers surrendered to the king who divided the lands all over again and gave them to separate people who were all the same people. Sort of. Probably.

Let that be a lesson to you all.

Friday, 31 January 2020

Awkward arrangements

The Dragon of Chirk (1)

Llywelyn Fychan ap Gruffudd, called the Dragon of Chirk by the poet Llygad Gwr, was one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Madog of Bromfield. When crisis engulfed Wales in 1276, Llywelyn was the first of his brothers to reach an accomodation with Edward I.

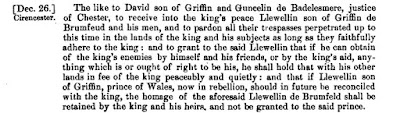

The terms of his submission (above) were brokered by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Guncelin Badlesmere, justice of Chester. It stipulated that should Llywelyn be reconciled with his namesake, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, his homage would not revert to the Prince of Wales. Instead it would be retained by the king and his heirs, so that Llywelyn’s lands would no longer be part of the principality of Wales.

These unusual terms indicate the depth of Llywelyn’s anger against his prince. It probably stemmed from the division of Powys Fadog in 1270, when Llywelyn’s brother Madog was granted a bigger slice of the territory than himself. Madog was the prince’s brother-in-law and hence more important, so it was unsurprising that he should come first.

There was also the thorny issue of Castell Dinas Bran. After their father’s death, Llywelyn and Madog had come to an awkward arrangement over possession of the castle. The castle stood inside the northern border of Nanheuwdwy, inside the lands of Llywelyn Fychan. However, it had somehow passed into the hands of Madog, though Llywelyn was allowed to occupy a part of it. This unsatisfactory agreement mirrored conditions in Gascony, where the existence of so many gentry obliged them to share their castles.

Finally, Madog agreed to give his brother Llywelyn the value of the castle in land. This was according to the decision of Prince Dafydd and Peter de Montfort; at this point Dafydd appears to have acted as Prince Llywelyn’s ‘viceroy’ in northern Powys, with jurisdiction over the local princes.

Llywelyn Fychan ap Gruffudd, called the Dragon of Chirk by the poet Llygad Gwr, was one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Madog of Bromfield. When crisis engulfed Wales in 1276, Llywelyn was the first of his brothers to reach an accomodation with Edward I.

The terms of his submission (above) were brokered by Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Guncelin Badlesmere, justice of Chester. It stipulated that should Llywelyn be reconciled with his namesake, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, his homage would not revert to the Prince of Wales. Instead it would be retained by the king and his heirs, so that Llywelyn’s lands would no longer be part of the principality of Wales.

These unusual terms indicate the depth of Llywelyn’s anger against his prince. It probably stemmed from the division of Powys Fadog in 1270, when Llywelyn’s brother Madog was granted a bigger slice of the territory than himself. Madog was the prince’s brother-in-law and hence more important, so it was unsurprising that he should come first.

|

| The arms of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd |

There was also the thorny issue of Castell Dinas Bran. After their father’s death, Llywelyn and Madog had come to an awkward arrangement over possession of the castle. The castle stood inside the northern border of Nanheuwdwy, inside the lands of Llywelyn Fychan. However, it had somehow passed into the hands of Madog, though Llywelyn was allowed to occupy a part of it. This unsatisfactory agreement mirrored conditions in Gascony, where the existence of so many gentry obliged them to share their castles.

Finally, Madog agreed to give his brother Llywelyn the value of the castle in land. This was according to the decision of Prince Dafydd and Peter de Montfort; at this point Dafydd appears to have acted as Prince Llywelyn’s ‘viceroy’ in northern Powys, with jurisdiction over the local princes.

Thursday, 30 January 2020

The Pillar of Eliseg

Castell Dinas Bran, high above the Dee valley near Llangollen. One of the earliest notices of the castle is in December 1270, when the heirs of Gruffudd ap Madog confirmed grants that their father had made to his wife, Emma Audley. The deed is dated at Dinas Bran, which means that enough of a structure must have existed by then; otherwise the family would have gathered on an exposed hilltop, which seems unlikely.

The reasons for building a stone castle on this lofty perch were twofold. It overlooked the dynastic abbey of Valle Crucis and the pillar or cross of Eliseg, suggesting the lords of Powys Fadog regarded this area as the cradle of their dynasty. Second, the castle shows traces of design influences from Gwynedd, and may have been intended as part of a defensive cordon of strongholds devised by Prince Llywelyn. These also included Ewloe, Dolforwyn, Bryn Amlwg and Rhyd y Briw. The D-tower at Dinas Bran is typical of the design of castles of the princes of Gwynedd.

Gruffudd had died in 1269. Hailed as “potens et prudens” - powerful and discreet - by chroniclers, his loss was a severe blow to Prince Llywelyn, who had already lost another valued advisor, Goronwy ab Ednyfed, in the previous year. The death of these men in quick succession may have been key to Llywelyn’s downfall, since his fortunes declined from 1269 onward.

Following the death of Gruffudd, his lordship was divided among four of his sons. Prince Llywelyn gave Maelor Gymraeg and Maelor Saesneg to Madog, and half of Glyndyfrdwy. Llywelyn Fychan, the Dragon of Chirk, got Nanheudwy, part of Cynllaith, part of Mochnant and Carreghofa. Gruffydd Fychan, a direct ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, got part of Glyndyfrdwy and Ial, while Owain got Bangor Is Coed and another part of Cynllaith. Madog’s primacy among the brothers is shown in the record of the trial of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn in 1274, where Madog witnessed the main record of the trial.

The reasons for building a stone castle on this lofty perch were twofold. It overlooked the dynastic abbey of Valle Crucis and the pillar or cross of Eliseg, suggesting the lords of Powys Fadog regarded this area as the cradle of their dynasty. Second, the castle shows traces of design influences from Gwynedd, and may have been intended as part of a defensive cordon of strongholds devised by Prince Llywelyn. These also included Ewloe, Dolforwyn, Bryn Amlwg and Rhyd y Briw. The D-tower at Dinas Bran is typical of the design of castles of the princes of Gwynedd.

Gruffudd had died in 1269. Hailed as “potens et prudens” - powerful and discreet - by chroniclers, his loss was a severe blow to Prince Llywelyn, who had already lost another valued advisor, Goronwy ab Ednyfed, in the previous year. The death of these men in quick succession may have been key to Llywelyn’s downfall, since his fortunes declined from 1269 onward.

Following the death of Gruffudd, his lordship was divided among four of his sons. Prince Llywelyn gave Maelor Gymraeg and Maelor Saesneg to Madog, and half of Glyndyfrdwy. Llywelyn Fychan, the Dragon of Chirk, got Nanheudwy, part of Cynllaith, part of Mochnant and Carreghofa. Gruffydd Fychan, a direct ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, got part of Glyndyfrdwy and Ial, while Owain got Bangor Is Coed and another part of Cynllaith. Madog’s primacy among the brothers is shown in the record of the trial of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn in 1274, where Madog witnessed the main record of the trial.

Wednesday, 29 January 2020

Elderly Welsh harpists

“The historians doubt it, but it strongly stands in the legend that Edward I of England sent 500 Welsh bards to the stake after his victory over the Welsh (1277) to prevent them from arousing the country and destroying English rule by telling of the glorious past of their nation.”

-

Janos Anary, the Hungarian poet who wrote The Bards of Wales (A walesi wárdok).

In this famous poem, composed in 1857, Edward Longshanks has a gigantic hissy fit and orders all the bards in Wales to be burnt at the stake. The poem was really meant as an analogy for Hapsburg control of Hungary and the repressive policies of Alexander von Bach, but the legend of flash-fried Welsh bards still finds the occasional echo today.

If any bard of Edward’s day was lined up for the stake, that man was surely Llygad Gwr. Llygad had been the court poet of Gruffudd ap Madog, whom the king must have regarded as a traitor; Gruffudd spent decades in English service before arranging the slaughter of Edward’s soldiers at Cymerau and defecting to Prince Llywelyn. Llygad also composed praise songs for Llywelyn, reckoned the most ‘nationalist’ poetry in Wales before the days of Owain Glyn Dwr.

Even so, it seems the wicked tyrant had bigger fish to fry than an elderly Welsh harpist. Surviving tax rolls (attached) show that Llygad Gwyr - “Legeth gour”, in the clumsy spelling of an English clerk - was alive and well in the vill of Carrog in the parish of Corwen in 1291. This makes sense, since Corwen lay inside the territory of Edeirnion, once held by Llygad’s old master Gruffudd ap Madog.

The record shows that Llygad, who must have been a very old man by 1291, paid 2 shillings 8.5 pence in tax: a good example of the excruciating attention to detail of the new royal administration in Wales. As such he was the second highest taxpayer in the vill after Madog ab Gruffydd Mal. This man could possibly be identified as Madog Grupl, Glyn Dwr’s great-grandfather.

Thus it seems that King Ted preferred to charge the bards of Wales VAT rather than chase them with a packet of firelighters. Within three generations Welsh poets such as Iolo Goch were composing praise poems to Edward’s descendents. For money, of course; what goes round comes round.

Janos Anary, the Hungarian poet who wrote The Bards of Wales (A walesi wárdok).

In this famous poem, composed in 1857, Edward Longshanks has a gigantic hissy fit and orders all the bards in Wales to be burnt at the stake. The poem was really meant as an analogy for Hapsburg control of Hungary and the repressive policies of Alexander von Bach, but the legend of flash-fried Welsh bards still finds the occasional echo today.

If any bard of Edward’s day was lined up for the stake, that man was surely Llygad Gwr. Llygad had been the court poet of Gruffudd ap Madog, whom the king must have regarded as a traitor; Gruffudd spent decades in English service before arranging the slaughter of Edward’s soldiers at Cymerau and defecting to Prince Llywelyn. Llygad also composed praise songs for Llywelyn, reckoned the most ‘nationalist’ poetry in Wales before the days of Owain Glyn Dwr.

Even so, it seems the wicked tyrant had bigger fish to fry than an elderly Welsh harpist. Surviving tax rolls (attached) show that Llygad Gwyr - “Legeth gour”, in the clumsy spelling of an English clerk - was alive and well in the vill of Carrog in the parish of Corwen in 1291. This makes sense, since Corwen lay inside the territory of Edeirnion, once held by Llygad’s old master Gruffudd ap Madog.

The record shows that Llygad, who must have been a very old man by 1291, paid 2 shillings 8.5 pence in tax: a good example of the excruciating attention to detail of the new royal administration in Wales. As such he was the second highest taxpayer in the vill after Madog ab Gruffydd Mal. This man could possibly be identified as Madog Grupl, Glyn Dwr’s great-grandfather.

Thus it seems that King Ted preferred to charge the bards of Wales VAT rather than chase them with a packet of firelighters. Within three generations Welsh poets such as Iolo Goch were composing praise poems to Edward’s descendents. For money, of course; what goes round comes round.

The crowned one of Mathrafal

The closeness of the relationship between Gruffudd ap Madog and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was made apparent in 1258, when Llywelyn proposed to marry his sister Margaret to his new ally. Gruffudd also took the opportunity to seize those lands in Powys that had been held by his brothers, especially those of Hywel. Consequently Hywel ap Madog remained loyal to the English and received cash gifts from Henry III. In October Henry wrote to Hywel condoning his efforts to recover his lost lands, but warned him not to disturb the truce that existed between the king and the Welsh. Quite how Hywel was supposed to take back his lands without disturbing the peace is unclear, but he was doubtless grateful for the money.

The parity or partnership with equals between Llywelyn and Gruffudd could not last long. Llywelyn first assumed the title Prince of Wales in March 1258, in an agreement between Scottish and Welsh lords in which Gruffudd was named third in the list of Welsh rulers, after Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd. A man who would be king (or prince) could have no equals, and Gruffudd found himself slowly relegated to the B-list.

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:

“Gruffudd…a ddalio Powys” (may Gruffudd hold Powys)

“Ohonawd henyw dadanudd” (the recovery of a patrimony springs from you)

In a slightly later poem, Llygad changes his tune somewhat and praises Llywelyn as supreme in Gwynedd and the war-leader active from Pulford to Cydweli. He is also praised as the “crowned one of Mathrafal”. Mathrafal, at least as far as Gwynedd jurists were concerned, was the chief court of Powys.

Llywelyn’s influence in Powys was also demonstrated by his agreement with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn in December 1263. Among the lands Llywelyn restored to Gruffudd was Deuddwr, part of Y Tair Swydd. Deuddwr had been a bone of contention between Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog, and Llywelyn chose to award it to the former.

[The grassy bump in the ground is all that remains of Mathrafal castle]

The parity or partnership with equals between Llywelyn and Gruffudd could not last long. Llywelyn first assumed the title Prince of Wales in March 1258, in an agreement between Scottish and Welsh lords in which Gruffudd was named third in the list of Welsh rulers, after Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd. A man who would be king (or prince) could have no equals, and Gruffudd found himself slowly relegated to the B-list.

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:

“Gruffudd…a ddalio Powys” (may Gruffudd hold Powys)

“Ohonawd henyw dadanudd” (the recovery of a patrimony springs from you)

In a slightly later poem, Llygad changes his tune somewhat and praises Llywelyn as supreme in Gwynedd and the war-leader active from Pulford to Cydweli. He is also praised as the “crowned one of Mathrafal”. Mathrafal, at least as far as Gwynedd jurists were concerned, was the chief court of Powys.

Llywelyn’s influence in Powys was also demonstrated by his agreement with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn in December 1263. Among the lands Llywelyn restored to Gruffudd was Deuddwr, part of Y Tair Swydd. Deuddwr had been a bone of contention between Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog, and Llywelyn chose to award it to the former.

[The grassy bump in the ground is all that remains of Mathrafal castle]

Tuesday, 28 January 2020

Playing a double game

On 2 June 1257 an English army under the leadership of Stephen Bauzan was destroyed at Cymerau in southwest Wales. The potential role of Gruffudd ap Madog, lord of Bromfield, in achieving this victory is often ignored.

Up until very recently Gruffudd had been a crown loyalist. He appears to have despised Llywelyn the Great and his successor, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, on account of their ill-treatment of Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffudd. After Gruffudd’s fatal plunge from the Tower or London, Gruffudd ap Madog’s attitude slowly changed.

In the early summer of 1257 Gruffudd apparently remained on active on behalf of Henry III. Along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, he was ordered by the king to assist John de Grey in the defence of the marchlands. Gruffudd ap Madog took charge of the border lordship of Kinnerley from his brother-in-law James Audley. He was only able to hold it for a month before being driven out by the invasion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In June, very shortly before the English defeat at Cymerau, Gruffudd was still receiving grants of English territory in the midlands as compensation for his losses.

Matthew Paris wrote that the victory of Cymerau was achieved ‘by the advice and instruction’ of Gruffudd ap Madog. Paris cannot be trusted, but had clearly heard a story of Gruffudd playing a double game. Some suggestive evidence can be found in Henry III’s correspondence. On 8 August the king made arrangements to receive Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn’s brother, whom Henry believed was about to defect to his side. One of the witnesses on this letter is Gruffudd ap Madog. He was clearly party to this plan. Another letter to this effect was issued on 25 August.

Gruffudd’s name does not appear on this second letter. On 20 September his chaplain was ordered to tear up both letters, since Dafydd had not come to the king. Just over a week later, according to the Annals of Chester, Gruffudd defected to Prince Llywelyn.

Up until very recently Gruffudd had been a crown loyalist. He appears to have despised Llywelyn the Great and his successor, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, on account of their ill-treatment of Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffudd. After Gruffudd’s fatal plunge from the Tower or London, Gruffudd ap Madog’s attitude slowly changed.

In the early summer of 1257 Gruffudd apparently remained on active on behalf of Henry III. Along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, he was ordered by the king to assist John de Grey in the defence of the marchlands. Gruffudd ap Madog took charge of the border lordship of Kinnerley from his brother-in-law James Audley. He was only able to hold it for a month before being driven out by the invasion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In June, very shortly before the English defeat at Cymerau, Gruffudd was still receiving grants of English territory in the midlands as compensation for his losses.

Matthew Paris wrote that the victory of Cymerau was achieved ‘by the advice and instruction’ of Gruffudd ap Madog. Paris cannot be trusted, but had clearly heard a story of Gruffudd playing a double game. Some suggestive evidence can be found in Henry III’s correspondence. On 8 August the king made arrangements to receive Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn’s brother, whom Henry believed was about to defect to his side. One of the witnesses on this letter is Gruffudd ap Madog. He was clearly party to this plan. Another letter to this effect was issued on 25 August.

Gruffudd’s name does not appear on this second letter. On 20 September his chaplain was ordered to tear up both letters, since Dafydd had not come to the king. Just over a week later, according to the Annals of Chester, Gruffudd defected to Prince Llywelyn.

Monday, 27 January 2020

An expression of incoherence

The peace of Amiens (3)

The third territory to be recovered by the English via the Treaty of Amiens in 1279 was the Agenais. This lay south of Périgord and in ancient Gaul was known as the country of the Nitiobriges, with Aginnum for their capital; in the fourth century AD it was part of the Roman province of Aquitaina Secunda and formed the diocese of Agen.

In 1152 the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II brought Agen into the vast family conglomerate known to later generations as the Angevin Empire. In 1212, during the Albigensian crusade, Simon de Montfort senior captured Penne-d’Agenais and burnt heretics at the stake. Via the Treaty of Paris in 1259 King Louis of France agreed to pay rent to Henry III of England for Agen, but in 1271 it should have passed to the English crown after the death of Joan of Poitiers. Instead the French hung on to it, as they did the Saintonge and other territories.

Edward I set about prising his rights from the grasp of Philip III, Louis’s successor. Philip was amenable and in August 1279 agreed to transfer Agen to the English. The transfer from one jurisdiction to another was a complex process. It began immediately after the treaty of Amiens was sealed (May 1279) and the task was entrusted to Edward’s uncle, William de Valence. The actual details were worked out by Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, and the bishop of Agen. On 9 August the proctors of the two kings met in the cloister of Agen in the presence of local clergy and lords, and representatives of the towns, the counts of Armagnac and Bigorre and other Gascon lords.

Here the transfer was announced. The seneschal of the king of France formally stripped himself of his duties and handed over to the English the revenues of the Agenais accrued since the date of the treaty (23 May). There was a slight hiccup when it was announced that a Gascon, the lord of Bergerac, would be the new seneschal. He was not a popular man, so Grailly smoothed things over by taking on the post himself for the time being.

The recovery of the Agenais gave Edward control of the Garonne, on which the city of Agen lies, and of its northern tributary, the Lot. Périgord lay to the north, the combined fiefs of Armagnac and Fezenac (held of Edward as duke of Aquitaine) to the south. It was a land of interlocking jurisdictions, described by the Anglo-French historian G.P. Cuttino as ‘an expression of incoherence’.

The third territory to be recovered by the English via the Treaty of Amiens in 1279 was the Agenais. This lay south of Périgord and in ancient Gaul was known as the country of the Nitiobriges, with Aginnum for their capital; in the fourth century AD it was part of the Roman province of Aquitaina Secunda and formed the diocese of Agen.

|

| The city of Agen |

In 1152 the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II brought Agen into the vast family conglomerate known to later generations as the Angevin Empire. In 1212, during the Albigensian crusade, Simon de Montfort senior captured Penne-d’Agenais and burnt heretics at the stake. Via the Treaty of Paris in 1259 King Louis of France agreed to pay rent to Henry III of England for Agen, but in 1271 it should have passed to the English crown after the death of Joan of Poitiers. Instead the French hung on to it, as they did the Saintonge and other territories.

Edward I set about prising his rights from the grasp of Philip III, Louis’s successor. Philip was amenable and in August 1279 agreed to transfer Agen to the English. The transfer from one jurisdiction to another was a complex process. It began immediately after the treaty of Amiens was sealed (May 1279) and the task was entrusted to Edward’s uncle, William de Valence. The actual details were worked out by Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, and the bishop of Agen. On 9 August the proctors of the two kings met in the cloister of Agen in the presence of local clergy and lords, and representatives of the towns, the counts of Armagnac and Bigorre and other Gascon lords.

|

| The Garonne river |

Here the transfer was announced. The seneschal of the king of France formally stripped himself of his duties and handed over to the English the revenues of the Agenais accrued since the date of the treaty (23 May). There was a slight hiccup when it was announced that a Gascon, the lord of Bergerac, would be the new seneschal. He was not a popular man, so Grailly smoothed things over by taking on the post himself for the time being.

The recovery of the Agenais gave Edward control of the Garonne, on which the city of Agen lies, and of its northern tributary, the Lot. Périgord lay to the north, the combined fiefs of Armagnac and Fezenac (held of Edward as duke of Aquitaine) to the south. It was a land of interlocking jurisdictions, described by the Anglo-French historian G.P. Cuttino as ‘an expression of incoherence’.

Sunday, 26 January 2020

The bridge over Saintonge

The peace of Amiens (2)

Saintonge, on the west central Atlantic coast of France, was another territory that ought to have ceded to the English via the Treaty of Paris. In August 1279, after the talks at Amiens, Philip III agreed to relinquish part of Saintonge to Edward I. This involved the recognition of Edward’s lordship over all the lands which Alphonse of Poitiers and his heirs had held south of the river Charente.

Philip’s nobles didn’t like to see their king making so many concessions. Two years later the parlement at Paris tried to get out of the deal, by ruling that any fiefs south of the Charente held of lords on the French side of the river should owe homage to their chief lord, rather than the king of England. This ruling appears to have been ignored or quietly put aside, and Edward continued to hold the territory until 1294.

Trouble started in 1293. The treaty of Amiens effectively cut Saintonge in two, with the English in control of the left side of the river and the French the right. The nominal capital on the English side was Saintes, seat of the former comital power, where Edward’s seneschal Rostand de Soler ruled in the king’s name.

The Saintes bridge over the Charente literally divided it into an English and a French town. This division was important, since it allowed Norman pirates to attack the English side and then use the French side as a safe haven. The Charente river was one of the primary locations for picking up wine to be taken north, and so an ideal target for piracy.

In a surviving report submitted by Rostand to Edward in 1293, the seneschal describes a campaign of terror waged by Norman pirates against English-held Saintonge:

“Armed with crossbows, swords, falchions and lances, and clad in haketons and bascinets, they entered the Charente river and soon started wreaking havoc.”

English chroniclers accused Philip le Bel’s brother, Charles of Valois, of deliberately egging on the pirates to provoke a war between England and France. The Chronicle of Lanercost even alleged that he desired to replace his brother as king of France, and hated the English because Edward supported Philip.

Saintonge, on the west central Atlantic coast of France, was another territory that ought to have ceded to the English via the Treaty of Paris. In August 1279, after the talks at Amiens, Philip III agreed to relinquish part of Saintonge to Edward I. This involved the recognition of Edward’s lordship over all the lands which Alphonse of Poitiers and his heirs had held south of the river Charente.

Philip’s nobles didn’t like to see their king making so many concessions. Two years later the parlement at Paris tried to get out of the deal, by ruling that any fiefs south of the Charente held of lords on the French side of the river should owe homage to their chief lord, rather than the king of England. This ruling appears to have been ignored or quietly put aside, and Edward continued to hold the territory until 1294.

Trouble started in 1293. The treaty of Amiens effectively cut Saintonge in two, with the English in control of the left side of the river and the French the right. The nominal capital on the English side was Saintes, seat of the former comital power, where Edward’s seneschal Rostand de Soler ruled in the king’s name.

The Saintes bridge over the Charente literally divided it into an English and a French town. This division was important, since it allowed Norman pirates to attack the English side and then use the French side as a safe haven. The Charente river was one of the primary locations for picking up wine to be taken north, and so an ideal target for piracy.

|

| Charles of Valois |

In a surviving report submitted by Rostand to Edward in 1293, the seneschal describes a campaign of terror waged by Norman pirates against English-held Saintonge:

“Armed with crossbows, swords, falchions and lances, and clad in haketons and bascinets, they entered the Charente river and soon started wreaking havoc.”

English chroniclers accused Philip le Bel’s brother, Charles of Valois, of deliberately egging on the pirates to provoke a war between England and France. The Chronicle of Lanercost even alleged that he desired to replace his brother as king of France, and hated the English because Edward supported Philip.

Saturday, 25 January 2020

Powicke on Henry

Maurice Powicke on Henry III:

“In spite of his faults he was never corrupted. If the child was father to the man, he was an inquisitive boy, observant of men and things about him, appreciative of beauty and form, especially in jewel and metal-work, attentive to detail in apparel, decoration, and ceremonial. He was affecionate and trustful by nature, but impulsive, easily distracted, and hot-tempered. His suspicion, his brooding memory of injuries long after they were generally forgotten, like his grateful reliance upon the few whom he felt he could really trust, may well have been fostered by his experiences as a boy in a court disturbed by the cross-currents of jealousy, faction, and ambition. He was easily frightened and disposed to swing violently from one side to another. He was not generous, though he was lavish; he was poor in judgement, though quick in perception; he was not magnaminous, though he could be dignified and decorous; he was devout rather than spiritually minded. Yet, when all has been said, Henry remains a decent man, and, in his way, a man to be reckoned with. He got through all his troubles and left England more prosperous, more united, more beautiful than it was when he was a child.”

- The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307

Whether one agrees with any or all of the above, Powicke’s description of Henry is full of nuances, which in turn stimulates thought (or should). Good for Powicke, say I.

“In spite of his faults he was never corrupted. If the child was father to the man, he was an inquisitive boy, observant of men and things about him, appreciative of beauty and form, especially in jewel and metal-work, attentive to detail in apparel, decoration, and ceremonial. He was affecionate and trustful by nature, but impulsive, easily distracted, and hot-tempered. His suspicion, his brooding memory of injuries long after they were generally forgotten, like his grateful reliance upon the few whom he felt he could really trust, may well have been fostered by his experiences as a boy in a court disturbed by the cross-currents of jealousy, faction, and ambition. He was easily frightened and disposed to swing violently from one side to another. He was not generous, though he was lavish; he was poor in judgement, though quick in perception; he was not magnaminous, though he could be dignified and decorous; he was devout rather than spiritually minded. Yet, when all has been said, Henry remains a decent man, and, in his way, a man to be reckoned with. He got through all his troubles and left England more prosperous, more united, more beautiful than it was when he was a child.”

- The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307

Whether one agrees with any or all of the above, Powicke’s description of Henry is full of nuances, which in turn stimulates thought (or should). Good for Powicke, say I.

Friday, 24 January 2020

Peace and settlement

The peace of Amiens (1)

On 23 May 1279 two kings, Philip III of France and Edward I of England, met at Amiens to discuss the settlement of the English king’s rights. Via the treaty of Paris in 1259, Edward was owed certain lands in France after the death of Alphonse of Poitiers and his wife, Joan. Alphonse and Joan had died within days of each other in 1271, but the French had held onto the outstanding territories.

Among Edward’s claims were the three dioceses of Limoges, Perigueux and Quercy. Limoges was a particular bone of contention, and had triggered the brief conflict in the Limousin I described in previous posts. That ended with Edward having to pay war damages to Philip.

In the new agreement at Amiens, Edward abandoned his claims to the three dioceses, so long as he could retain the fealty of those inhabitants who wished to remain vassals of the English crown. This was in order to keep his promise, made in 1274, not to abandon the bourgoise of Limoges. Those who maintained their fealty to Edward were called the privileged or ‘privilegiati’.

Philip, in his turn, agreed to waive one of the most troublesome conditions of the treaty of Paris. This was an obligation placed upon Edward, as duke of Aquitaine, to extract from his vassals in France an oath to the king of France that they would oppose the duke if he failed to uphold the treaty. In other words, Edward was obliged to make his own subjects agree to fight him on behalf of the French. He used persuasion, threats and intimidation to get them to swear this oath, but they refused. Finally, at Amiens, Philip agreed to drop this absurd clause and let it lie.

The issue was not finally settled until 1286 when Philip’s successor, Philip le Bel, confirmed Edward’s lordship over the privileged of the three dioceses. Thus all was settled amicably and with gain on both sides; a typically subtle political arrangement of the time. Don’t expect it to appear on Netflix anytime soon.

On 23 May 1279 two kings, Philip III of France and Edward I of England, met at Amiens to discuss the settlement of the English king’s rights. Via the treaty of Paris in 1259, Edward was owed certain lands in France after the death of Alphonse of Poitiers and his wife, Joan. Alphonse and Joan had died within days of each other in 1271, but the French had held onto the outstanding territories.

Among Edward’s claims were the three dioceses of Limoges, Perigueux and Quercy. Limoges was a particular bone of contention, and had triggered the brief conflict in the Limousin I described in previous posts. That ended with Edward having to pay war damages to Philip.

|

| Philip III |

In the new agreement at Amiens, Edward abandoned his claims to the three dioceses, so long as he could retain the fealty of those inhabitants who wished to remain vassals of the English crown. This was in order to keep his promise, made in 1274, not to abandon the bourgoise of Limoges. Those who maintained their fealty to Edward were called the privileged or ‘privilegiati’.

Philip, in his turn, agreed to waive one of the most troublesome conditions of the treaty of Paris. This was an obligation placed upon Edward, as duke of Aquitaine, to extract from his vassals in France an oath to the king of France that they would oppose the duke if he failed to uphold the treaty. In other words, Edward was obliged to make his own subjects agree to fight him on behalf of the French. He used persuasion, threats and intimidation to get them to swear this oath, but they refused. Finally, at Amiens, Philip agreed to drop this absurd clause and let it lie.

The issue was not finally settled until 1286 when Philip’s successor, Philip le Bel, confirmed Edward’s lordship over the privileged of the three dioceses. Thus all was settled amicably and with gain on both sides; a typically subtle political arrangement of the time. Don’t expect it to appear on Netflix anytime soon.

Thursday, 23 January 2020

The Two Eleanors

My review of The Two Eleanors of Henry III: the lives of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, by Darren Baker.

The Two Eleanors of Henry III by Darren Baker is a dual biography of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, respectively the wife and sister of Henry III of England (reigned 1216-72). It is an effort to focus on the lives of two high-ranking noblewomen of the era, as a welcome change from the usual male-dominated narratives. The book also casts a radically different light on the nature and motives of some of the famous protagonists of the era, notably Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester and chief driver of the reform movement in England.

Before reading this, I had noticed a few prickly reviews that complained of the difficulty of telling the two Eleanors apart in the narrative. Perceptions differ, of course, but I didn’t find it difficult to distinguish between them; any more than (for example) King Henry and his nephew Henry of Almaine. The Eleanors were alike in some respects: forceful, intelligent, a great influence on their husbands, but they led very different lives.

It is true that the Eleanors are sometimes overshadowed by their husbands in the text, but that is inevitable given the nature of the subject. Men typically wielded power - officially, at any rate - and it is easier to trace their actions. Even so, Baker quotes some remarkable letters and accounts for the women. These include a series of correspondence between Eleanor de Montfort and a stuffy cleric, Adam Marsh, who spent much of his time advising her to show humility, as a woman ‘should’, and not to argue with her spouse. Eleanor paid no attention and revelled in jewellery and expensive clothing. Neither Eleanor was afraid to clash with their husbands, and one particularly bitter row between Eleanor of Provence and Henry leaps off the page.

To his credit, Baker makes no effort to conceal the darker side of the Eleanors. Like her husband, Eleanor de Montfort was an oppressive landlord who evicted tenants and screwed down hard on the poor. Eleanor of Provence took blood money from the Jews and profited from the sale of Jewish bonds to Christians, one of the most notorious rackets of the age. She also had a tendency to appoint corrupt officials, such as Geoffrey Langley and Brother William of Tarentum, said to have ‘gaped after money like a horseleech after blood’. The appointment of Langley in North Wales proved a disaster, as his money-grubbing and efforts to shire the Four Cantreds triggered a full-scale Welsh revolt.

Money is a dominant theme. Everyone is out to get it, especially the Montforts. I have never been a great fan of Simon and his hair shirt, but hadn’t realised quite how grasping and deceitful the man was. He and his wife attempted to sabotage the Treaty of Paris, one of the great peace agreements of the age, simply to pressure Henry to satisfy outstanding claims for cash. Simon also comes across as a crude bully who routinely threatened opponents in council with physical violence. He betrayed and undermined Henry on several occasions, planted an agent in Rome to secretly work against the king, and generally pursued his own self-interest at all times. So much for Saint Simon.

Baker also deprives Simon of his greatest glory i.e. his alleged status as the founder of parliamentary democracy in England. This honour actually belongs to Eleanor of Provence. In 1254, while Henry was abroad, the queen presided over the first democratic mandate in England. This was over a decade before Simon’s famous assemblies, an inconvenient fact that appears to have been brushed under the carpet.

If I have a criticism, it is that the first third of the book is a little slow. This is partially due to the youth of the protagonists: Eleanor of Provence was only 12 when she married Henry, and naturally had little influence until she matured. Simon, meanwhile, is little more than a hopeful foreign adventurer angling for a rich bride. Henry’s reign itself is a bit of a grind for the first decade, as the young king struggles to assert himself and has to cope with the machinations of his nobles, including the remarkably unpleasant Richard Marshall. The pace picks up from about 1235 onwards, when the personalities of the two duelling couples really come into their own. The most interesting figure at this early stage is Blanche of Castile, the formidable queen of France, who effortlessly unpicked Henry’s attempts to forge dynastic alliances in France. A biography of Blanche would be most welcome.

The climax is reached in the great power-struggle of the reform period, when Henry and Simon (and their wives) ended up at daggers drawn. This was a tragedy on a personal as well as national level, as two couples who had known each other for decades ended up as bitter enemies. Their problems are exacerbated by the rise of Henry’s heir, a wayward tyro named Edward Longshanks. For a king who would have no favourites, Edward was surprisingly malleable at this stage, dragged about by various factions in his pursuit of independence. His infatuation with Simon caused his parents endless heartache, until the scales fell from his eyes when Queen Eleanor was almost killed by a mob in London, stirred up by Montfortian sympathizers. The slaughter of Evesham - more of a mass execution than a battle - lumbered Edward with a blood-feud, though he did his best to reconcile Simon’s widow and her children.

Overall this is an epic tale, recounting four extraordinary intertwined lives, and how their successes and failures wrought permanent changes in England. It ends on a slightly melancholy note, with both Eleanors relegated to the background in their declining years. Perhaps the author could have made a little more of Eleanor de Montfort’s last significant decision, the marriage alliance with Prince Llywelyn of Wales, although the consequences of that might easily fill a separate book. The Two Eleanors does a fine job of shining an overdue light on two fascinating and powerful - in the true sense of the word - medieval noblewomen.

The Two Eleanors of Henry III by Darren Baker is a dual biography of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, respectively the wife and sister of Henry III of England (reigned 1216-72). It is an effort to focus on the lives of two high-ranking noblewomen of the era, as a welcome change from the usual male-dominated narratives. The book also casts a radically different light on the nature and motives of some of the famous protagonists of the era, notably Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester and chief driver of the reform movement in England.

Before reading this, I had noticed a few prickly reviews that complained of the difficulty of telling the two Eleanors apart in the narrative. Perceptions differ, of course, but I didn’t find it difficult to distinguish between them; any more than (for example) King Henry and his nephew Henry of Almaine. The Eleanors were alike in some respects: forceful, intelligent, a great influence on their husbands, but they led very different lives.

It is true that the Eleanors are sometimes overshadowed by their husbands in the text, but that is inevitable given the nature of the subject. Men typically wielded power - officially, at any rate - and it is easier to trace their actions. Even so, Baker quotes some remarkable letters and accounts for the women. These include a series of correspondence between Eleanor de Montfort and a stuffy cleric, Adam Marsh, who spent much of his time advising her to show humility, as a woman ‘should’, and not to argue with her spouse. Eleanor paid no attention and revelled in jewellery and expensive clothing. Neither Eleanor was afraid to clash with their husbands, and one particularly bitter row between Eleanor of Provence and Henry leaps off the page.

To his credit, Baker makes no effort to conceal the darker side of the Eleanors. Like her husband, Eleanor de Montfort was an oppressive landlord who evicted tenants and screwed down hard on the poor. Eleanor of Provence took blood money from the Jews and profited from the sale of Jewish bonds to Christians, one of the most notorious rackets of the age. She also had a tendency to appoint corrupt officials, such as Geoffrey Langley and Brother William of Tarentum, said to have ‘gaped after money like a horseleech after blood’. The appointment of Langley in North Wales proved a disaster, as his money-grubbing and efforts to shire the Four Cantreds triggered a full-scale Welsh revolt.

Money is a dominant theme. Everyone is out to get it, especially the Montforts. I have never been a great fan of Simon and his hair shirt, but hadn’t realised quite how grasping and deceitful the man was. He and his wife attempted to sabotage the Treaty of Paris, one of the great peace agreements of the age, simply to pressure Henry to satisfy outstanding claims for cash. Simon also comes across as a crude bully who routinely threatened opponents in council with physical violence. He betrayed and undermined Henry on several occasions, planted an agent in Rome to secretly work against the king, and generally pursued his own self-interest at all times. So much for Saint Simon.

Baker also deprives Simon of his greatest glory i.e. his alleged status as the founder of parliamentary democracy in England. This honour actually belongs to Eleanor of Provence. In 1254, while Henry was abroad, the queen presided over the first democratic mandate in England. This was over a decade before Simon’s famous assemblies, an inconvenient fact that appears to have been brushed under the carpet.

If I have a criticism, it is that the first third of the book is a little slow. This is partially due to the youth of the protagonists: Eleanor of Provence was only 12 when she married Henry, and naturally had little influence until she matured. Simon, meanwhile, is little more than a hopeful foreign adventurer angling for a rich bride. Henry’s reign itself is a bit of a grind for the first decade, as the young king struggles to assert himself and has to cope with the machinations of his nobles, including the remarkably unpleasant Richard Marshall. The pace picks up from about 1235 onwards, when the personalities of the two duelling couples really come into their own. The most interesting figure at this early stage is Blanche of Castile, the formidable queen of France, who effortlessly unpicked Henry’s attempts to forge dynastic alliances in France. A biography of Blanche would be most welcome.

The climax is reached in the great power-struggle of the reform period, when Henry and Simon (and their wives) ended up at daggers drawn. This was a tragedy on a personal as well as national level, as two couples who had known each other for decades ended up as bitter enemies. Their problems are exacerbated by the rise of Henry’s heir, a wayward tyro named Edward Longshanks. For a king who would have no favourites, Edward was surprisingly malleable at this stage, dragged about by various factions in his pursuit of independence. His infatuation with Simon caused his parents endless heartache, until the scales fell from his eyes when Queen Eleanor was almost killed by a mob in London, stirred up by Montfortian sympathizers. The slaughter of Evesham - more of a mass execution than a battle - lumbered Edward with a blood-feud, though he did his best to reconcile Simon’s widow and her children.

Overall this is an epic tale, recounting four extraordinary intertwined lives, and how their successes and failures wrought permanent changes in England. It ends on a slightly melancholy note, with both Eleanors relegated to the background in their declining years. Perhaps the author could have made a little more of Eleanor de Montfort’s last significant decision, the marriage alliance with Prince Llywelyn of Wales, although the consequences of that might easily fill a separate book. The Two Eleanors does a fine job of shining an overdue light on two fascinating and powerful - in the true sense of the word - medieval noblewomen.

Was Ferrers the man in the Hood (1)?

Yesterday I posted an account of a Robin Hood ballad from the chronicle of Walter Bower, which placed the legendary outlaw in the year 1266, during the Montfortian wars in England.

Another interesting reference is The Pedigree of Robert Earle Fferrers and Derby. This obscure document dates from the mid-17th century and is a history of the medieval earls of Derby and their descendents. It is anonymous, but the text shows signs of being derived from an earlier source. The entry for Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby (1239-79) reads as follows:

“Upon a certaine day, but being not able to pay and perform the same, his said justiar assigned over their mortgage unto the said lord Edmund who ENTERED & enjoyed the said lands, whereupon this Earle Robert being discontented with some servants retired himself into the fforest of Sherwood and other places in the county of nottingham & darby living by robbery and depredations until he was outlawed, then being prosecuted he fledd northwards and for feare of being apprehended & taken, gott to the nunnerie of Kirklees in Yorkshire (now the inheritance of Sir John Armitage Baronet) where he concealed himself untill he opened a vaine (cancelled) some vaines and voluntarily bledd to death, and was buried in the open field neare the said nunnerie about seven miles from Wakefield, over whole grave is a stone with some obsolute letters not to be read and now to be soone called Robin Hoods grave & formerly an arbour of trees and wood.”

This refers to the earl’s disinheritance in 1269 in favour of Edmund of Lancaster, second son of Henry III. Ferrers is known to have led a band of outlaws in the High Peak in Derbyshire and other places, but the really interesting bit is the account of his death. In the early ballads, Robin Hood is treacherously bled to death at Kirklees priory. In the above snippet, Ferrers dies at Kirklees after bleeding himself to death. This appears to be a reference to his gout: a hereditary condition that was treated by bleeding the patient.

Thus, the life and death of Robert de Ferrers was merged with the legend of Robin Hood. Granted, the tradition is fairly late, but there are other clues.

Another interesting reference is The Pedigree of Robert Earle Fferrers and Derby. This obscure document dates from the mid-17th century and is a history of the medieval earls of Derby and their descendents. It is anonymous, but the text shows signs of being derived from an earlier source. The entry for Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby (1239-79) reads as follows:

“Upon a certaine day, but being not able to pay and perform the same, his said justiar assigned over their mortgage unto the said lord Edmund who ENTERED & enjoyed the said lands, whereupon this Earle Robert being discontented with some servants retired himself into the fforest of Sherwood and other places in the county of nottingham & darby living by robbery and depredations until he was outlawed, then being prosecuted he fledd northwards and for feare of being apprehended & taken, gott to the nunnerie of Kirklees in Yorkshire (now the inheritance of Sir John Armitage Baronet) where he concealed himself untill he opened a vaine (cancelled) some vaines and voluntarily bledd to death, and was buried in the open field neare the said nunnerie about seven miles from Wakefield, over whole grave is a stone with some obsolute letters not to be read and now to be soone called Robin Hoods grave & formerly an arbour of trees and wood.”

|

| The arms of Robert de Ferrers |

This refers to the earl’s disinheritance in 1269 in favour of Edmund of Lancaster, second son of Henry III. Ferrers is known to have led a band of outlaws in the High Peak in Derbyshire and other places, but the really interesting bit is the account of his death. In the early ballads, Robin Hood is treacherously bled to death at Kirklees priory. In the above snippet, Ferrers dies at Kirklees after bleeding himself to death. This appears to be a reference to his gout: a hereditary condition that was treated by bleeding the patient.

|

| Kirklees Priory |

Wednesday, 22 January 2020

Normal relations

Gaston and Llywelyn.

At Rhuddlan on 15 November 1277, five days after he had ratified the terms of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s submission, Edward I wrote to King Philip of France. His subject was the long-running saga of Gaston de Béarn, still with no end in sight.

Edward had sent Gaston back to France, in the expectation that he would be punished by Philip. The French king’s notion of punishment was to give Gaston seisin of his lands and castles and restore him to the allegiance of the king of England. As Edward had made clear in his letter, this was not the sentence he had been seeking from his cousin. It was all the more bizzare, since Philip had previously sent the Gascon rebel to England with a noose round his neck.

The letters composed at Rhuddlan laid great stress on Edward’s will (voluntas, volunte). They make for an interesting comparison to the terms of Llywelyn’s surrender: the Welsh prince had given himself up entirely to the will of the king - “supponet se voluntati et misericordie dicti domini regis.” This was written in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn’s total submission to the mercy of a king who was able to deal with an intransigent vassal directly, with overwhelming military force, and with no reference to any other secular power.

Gaston was also Edward’s vassal, but unlike Llywelyn he had two overlords. The English king could not pass sentence on him without reference to his French counterpart, and Philip was playing the situation to his advantage. From Paris, Edward’s seneschal reported that Philip was inquiring into matters in Gascony which were no concern of the French court; in short, he was using Gaston as an opportunity to extend French influence into the duchy.

With all this in mind, Edward changed his policy. He could not kill or disinherit Gaston, nor could he afford to let Philip exploit him. So, in March 1278, he received Gaston into his grace, restored his lands and castles and awarded him an annual fee of 2000 livres tournois from the customs of Bordeaux. This was the same fee Gaston had been awarded before the planned marriage of his daughter, Constance, to Henry of Almaine. That plan fell through when Henry was murdered in Italy by the Montfort brothers, but now Edward revived the stipend in an effort to resume normal relations.

The conciliation paid off: Gaston was well placed to serve Edward in Gascony and further afield, and became the king’s loyal servant. His many services as an envoy and military captain were awarded with the grant of Lados, an estate on the Gironde. He would eventually die in his bed of natural causes. Llywelyn was not half so fortunate.

At Rhuddlan on 15 November 1277, five days after he had ratified the terms of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s submission, Edward I wrote to King Philip of France. His subject was the long-running saga of Gaston de Béarn, still with no end in sight.

|

| Rhuddlan castle |

Edward had sent Gaston back to France, in the expectation that he would be punished by Philip. The French king’s notion of punishment was to give Gaston seisin of his lands and castles and restore him to the allegiance of the king of England. As Edward had made clear in his letter, this was not the sentence he had been seeking from his cousin. It was all the more bizzare, since Philip had previously sent the Gascon rebel to England with a noose round his neck.

The letters composed at Rhuddlan laid great stress on Edward’s will (voluntas, volunte). They make for an interesting comparison to the terms of Llywelyn’s surrender: the Welsh prince had given himself up entirely to the will of the king - “supponet se voluntati et misericordie dicti domini regis.” This was written in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn’s total submission to the mercy of a king who was able to deal with an intransigent vassal directly, with overwhelming military force, and with no reference to any other secular power.

Gaston was also Edward’s vassal, but unlike Llywelyn he had two overlords. The English king could not pass sentence on him without reference to his French counterpart, and Philip was playing the situation to his advantage. From Paris, Edward’s seneschal reported that Philip was inquiring into matters in Gascony which were no concern of the French court; in short, he was using Gaston as an opportunity to extend French influence into the duchy.

|

| The arms of Gwynedd |

With all this in mind, Edward changed his policy. He could not kill or disinherit Gaston, nor could he afford to let Philip exploit him. So, in March 1278, he received Gaston into his grace, restored his lands and castles and awarded him an annual fee of 2000 livres tournois from the customs of Bordeaux. This was the same fee Gaston had been awarded before the planned marriage of his daughter, Constance, to Henry of Almaine. That plan fell through when Henry was murdered in Italy by the Montfort brothers, but now Edward revived the stipend in an effort to resume normal relations.

The conciliation paid off: Gaston was well placed to serve Edward in Gascony and further afield, and became the king’s loyal servant. His many services as an envoy and military captain were awarded with the grant of Lados, an estate on the Gironde. He would eventually die in his bed of natural causes. Llywelyn was not half so fortunate.

Dispose of this man

Limoges and Béarn (8)

At the September 1274 parliament in Paris, Gaston de Béarn accused his overlord Edward I of being a traitor and a liar, and challenged him to single combat. He also prayed that the “King of England be chastised and made to suffer by the law of the land.”

Feudal suzerains were not in the habit of brawling with their vassals. To answer the challenge, Edward sent five knights to the French court charged to introduce themselves as his champions. A Gascon knight, Gilles de Noaillan, was so outraged he wrote a letter to the king, - “moun seigneur, le Roy de d’Engleterre” - requesting the honour of beating the crap out of the insolent viscomte. Gaston responded by declaring he would fight no-one except Edward himself.

The French king, presiding as judge, declared there would be no combat. Instead the adversaries were summoned to the next session of parlement at Candlemas.

King Philip was in a cleft stick. On the one hand, he rather enjoyed witnessing the embarassment of his cousin. On the other, Gaston was a pain in everyone’s backside and had done undeniable wrongs to his overlord. In the end Philip decided to throw the problem back at Edward, and in 1275 packed Gaston off to England for judgement.

There were suspicions over Philippe’s intentions. One of Edward’s lawyers in Paris, Pierre Odon, sent a stark warning to his master:

“You know how much Gaston offended you; take guard that he dare not do more from now on; otherwise the barons of Gascony would misuse it.”

Edward received all kinds of mixed messages. His aunt, Margaret of Provence, sent him a letter requesting Gaston be shown mercy. It seems Philip took the opposite view. When the captive finally turned up at Westminster, escorted by French soldiers, he had a noose round his neck. Dispose of this man, cousin Ned, was the not-very-subtle message.

Gaston was now at Edward’s mercy. He was brought before parliament and there renounced all his insults against the king. This was declared sufficient, and all proceedings at law were formally ended. Only one point remained: what punishment should be inflicted?

Edward promptly threw Gaston back at Philip.

At the September 1274 parliament in Paris, Gaston de Béarn accused his overlord Edward I of being a traitor and a liar, and challenged him to single combat. He also prayed that the “King of England be chastised and made to suffer by the law of the land.”

|

| Seal of Margaret of Provence |

Feudal suzerains were not in the habit of brawling with their vassals. To answer the challenge, Edward sent five knights to the French court charged to introduce themselves as his champions. A Gascon knight, Gilles de Noaillan, was so outraged he wrote a letter to the king, - “moun seigneur, le Roy de d’Engleterre” - requesting the honour of beating the crap out of the insolent viscomte. Gaston responded by declaring he would fight no-one except Edward himself.

The French king, presiding as judge, declared there would be no combat. Instead the adversaries were summoned to the next session of parlement at Candlemas.

King Philip was in a cleft stick. On the one hand, he rather enjoyed witnessing the embarassment of his cousin. On the other, Gaston was a pain in everyone’s backside and had done undeniable wrongs to his overlord. In the end Philip decided to throw the problem back at Edward, and in 1275 packed Gaston off to England for judgement.

There were suspicions over Philippe’s intentions. One of Edward’s lawyers in Paris, Pierre Odon, sent a stark warning to his master:

“You know how much Gaston offended you; take guard that he dare not do more from now on; otherwise the barons of Gascony would misuse it.”

Edward received all kinds of mixed messages. His aunt, Margaret of Provence, sent him a letter requesting Gaston be shown mercy. It seems Philip took the opposite view. When the captive finally turned up at Westminster, escorted by French soldiers, he had a noose round his neck. Dispose of this man, cousin Ned, was the not-very-subtle message.

Gaston was now at Edward’s mercy. He was brought before parliament and there renounced all his insults against the king. This was declared sufficient, and all proceedings at law were formally ended. Only one point remained: what punishment should be inflicted?

Edward promptly threw Gaston back at Philip.

Tuesday, 21 January 2020

Of cats and dogs

Limoges and Béarn (7)

In July 1274 William de Valence, Edward I’s Lusigan half-uncle, laid siege to Aixe castle in the Limousin with an army of Englishmen and French militia. The castle was defended by the soldiers of the Viscomtesse Marguerite of Limoges, also cooped up inside.

Valence brought an engineer, named Civry, who devised an interesting siege engine. This thing lobbed balls of burning sulphur, a weapon apparently not used again by the English until the siege of Brechin in Scotland in 1303. For nine days Civry’s invention pounded the walls, while the defenders hurled bits of timber and broken furniture down on the besiegers. Valence apparently kept his own men in reserve and let the militia do all the rough stuff: it was their fight, after all.

The siege ended abruptly on 24 July, when a herald from Paris ordered both parties to cease hostilities. Philippe le Hardi, king of France, had been slow to deal with the private war in Limoges, but now he took control of the affair. He ordered the king of England not to receive any more oaths of fealty from Limoges, not to block the justice of the Viscomtesse, not to protect the bourgeois and not to maintain a bailiff in the city.

To add insult to injury, the Candlemas parliament of 1275 ordered Edward to pay war damages amounting to 22, 613 livres tournois. It is difficult to figure out how much this was worth in English currency, but in the fifteenth century one English pound sterling was worth 8.5 times as much as the livres tournois. This gives a ballpark figure of £2600 Edward was required to pay - hefty enough, given that the average income of an English baron in this era was about £300 per annum.

On top of that was the political embarrassment. Edward had tried to act on principle in Limoges, and ended up being slapped with a bill for war damages. Philippe had not exactly been helpful, and the chronicler of Limoges remarked on the peculiar relationship of the two kings; there was, he said, a ‘cat-and-dog love between them’:

“Hic amor dici potest amor cati et canis.”

To add to Edward’s woes, Gaston de Béarn was still carping away in the background. Never one to accept defeat, Gaston had appealed to the French parlement against Edward, and appeared in person before Philip. Here he denounced the English king as a traitor, a liar and an unfair judge, and challenged him to single combat. In a final flourish, he literally threw down his gauntlet.

Gaston had really gone too far this time. There were certain rules to this game, and challenging one’s feudal overlord to a duel was not one of them.

In July 1274 William de Valence, Edward I’s Lusigan half-uncle, laid siege to Aixe castle in the Limousin with an army of Englishmen and French militia. The castle was defended by the soldiers of the Viscomtesse Marguerite of Limoges, also cooped up inside.

|

| The ruins of Aixe castle |

Valence brought an engineer, named Civry, who devised an interesting siege engine. This thing lobbed balls of burning sulphur, a weapon apparently not used again by the English until the siege of Brechin in Scotland in 1303. For nine days Civry’s invention pounded the walls, while the defenders hurled bits of timber and broken furniture down on the besiegers. Valence apparently kept his own men in reserve and let the militia do all the rough stuff: it was their fight, after all.

The siege ended abruptly on 24 July, when a herald from Paris ordered both parties to cease hostilities. Philippe le Hardi, king of France, had been slow to deal with the private war in Limoges, but now he took control of the affair. He ordered the king of England not to receive any more oaths of fealty from Limoges, not to block the justice of the Viscomtesse, not to protect the bourgeois and not to maintain a bailiff in the city.

To add insult to injury, the Candlemas parliament of 1275 ordered Edward to pay war damages amounting to 22, 613 livres tournois. It is difficult to figure out how much this was worth in English currency, but in the fifteenth century one English pound sterling was worth 8.5 times as much as the livres tournois. This gives a ballpark figure of £2600 Edward was required to pay - hefty enough, given that the average income of an English baron in this era was about £300 per annum.

On top of that was the political embarrassment. Edward had tried to act on principle in Limoges, and ended up being slapped with a bill for war damages. Philippe had not exactly been helpful, and the chronicler of Limoges remarked on the peculiar relationship of the two kings; there was, he said, a ‘cat-and-dog love between them’:

“Hic amor dici potest amor cati et canis.”

To add to Edward’s woes, Gaston de Béarn was still carping away in the background. Never one to accept defeat, Gaston had appealed to the French parlement against Edward, and appeared in person before Philip. Here he denounced the English king as a traitor, a liar and an unfair judge, and challenged him to single combat. In a final flourish, he literally threw down his gauntlet.

Gaston had really gone too far this time. There were certain rules to this game, and challenging one’s feudal overlord to a duel was not one of them.

Monday, 20 January 2020

The keys to the city

Limoges and Béarn (6)

After the surrender of Gaston de Béarn, Edward I turned about and went north, to deal with the situation at Limoges. On 10 May 1274 he entered the town and was received in ‘processionnellement’ (truimphal parade) by the bourgeois. Shortly after his arrival, abbots of the principal monasteries begged him to restore peace with the Viscomtesse.

Edward was wary of provoking an open breach with the French court, so he dispatched messengers to Paris. While he awaited their return, the soldiers of the Viscomtesse started to attack the bourgeois again. The Limousin was reduced to a pitiful state by this private war:

“All prices on commodities had increased; mortality was extreme; people had never seen so many robbers along the roads nor had they ever seen so many corbels (fortifications) defending the towers of churches.”

- Histoire de France, XXI

The bourgeois continued to beg Edward to defend them. He would do nothing until word arrived from Paris, so went off hunting in the mountains instead. When he came back, on 5 June, he found his messengers had returned empty handed. Philip refused to grant a truce, or even a letter.

The ball was left in Edward’s court. On 7 June the bourgeois made one last desperate plea and threw the keys of the city down before him. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Edward gave way to tears and released the people of Limoges from the oath they had given him. He could not, he said, disobey the King of France, but neither would he abandon those who wished to retain their fealty to the English crown.

His solution was to depart from Limoges, but leave most of his soldiers behind to defend the city. On 7 July his uncle William de Valence arrrived with two hundred English men-at-arms and an engineer, who started to construct war-machines. A few days later Valence led an army of Englishmen and bourgeois militia to attack the Viscomtesse.

After the surrender of Gaston de Béarn, Edward I turned about and went north, to deal with the situation at Limoges. On 10 May 1274 he entered the town and was received in ‘processionnellement’ (truimphal parade) by the bourgeois. Shortly after his arrival, abbots of the principal monasteries begged him to restore peace with the Viscomtesse.

Edward was wary of provoking an open breach with the French court, so he dispatched messengers to Paris. While he awaited their return, the soldiers of the Viscomtesse started to attack the bourgeois again. The Limousin was reduced to a pitiful state by this private war:

“All prices on commodities had increased; mortality was extreme; people had never seen so many robbers along the roads nor had they ever seen so many corbels (fortifications) defending the towers of churches.”

- Histoire de France, XXI

|

| The tomb of William de Valence |

The bourgeois continued to beg Edward to defend them. He would do nothing until word arrived from Paris, so went off hunting in the mountains instead. When he came back, on 5 June, he found his messengers had returned empty handed. Philip refused to grant a truce, or even a letter.

The ball was left in Edward’s court. On 7 June the bourgeois made one last desperate plea and threw the keys of the city down before him. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Edward gave way to tears and released the people of Limoges from the oath they had given him. He could not, he said, disobey the King of France, but neither would he abandon those who wished to retain their fealty to the English crown.

His solution was to depart from Limoges, but leave most of his soldiers behind to defend the city. On 7 July his uncle William de Valence arrrived with two hundred English men-at-arms and an engineer, who started to construct war-machines. A few days later Valence led an army of Englishmen and bourgeois militia to attack the Viscomtesse.

Complete submission

Limoges and Béarn (5)

After the collapse of his rebellion in Gascony, Gaston de Béarn fled south to take refuge in his castles on the edge of the Pyrenees. Edward I was in no hurry to follow. The war in Limoge was suspended, for the moment, so he could take his time in bringing the troublesome viscomte to heel.

On 14 December 1273 Edward was at Mimizan on the coast of Gascony, now part of the Landes department of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Here he granted the commune a charter, whereby in exchange for 200 livres angevin to help fund his war against Gaston, the king guaranteed that the menfolk of Mimizan would never have to do military service in the future. Such a concession might suggest the commune was tiny and of no military value, or that Edward took one look at the local youth and was only too glad to take the cash instead.

According to Rishanger, Edward then marched south to blockade Gaston in his strongest castle:

“Edward marched in great power with his army into Gaston's lands, forced him to flee, and besieged him in the strong and well-defended castle to which he had retreated.”

- William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

The castle in question was probably the Château Moncade, a castle and fortified bourg that Gaston had only started to build in 1242; ironically, with money granted by Henry III. Only part of the keep remains today, but it was quite impressive at the time (see pics).

Gaston’s brief revolt had collapsed into the dust. On 14 January 1274 he agreed to surrender via the mediation of a papal envoy, though the envoy could do no more than facilitate Gaston’s complete submission to the king’s will.

Thanks to Rich Price, as ever, for the various translations.

After the collapse of his rebellion in Gascony, Gaston de Béarn fled south to take refuge in his castles on the edge of the Pyrenees. Edward I was in no hurry to follow. The war in Limoge was suspended, for the moment, so he could take his time in bringing the troublesome viscomte to heel.

On 14 December 1273 Edward was at Mimizan on the coast of Gascony, now part of the Landes department of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Here he granted the commune a charter, whereby in exchange for 200 livres angevin to help fund his war against Gaston, the king guaranteed that the menfolk of Mimizan would never have to do military service in the future. Such a concession might suggest the commune was tiny and of no military value, or that Edward took one look at the local youth and was only too glad to take the cash instead.

According to Rishanger, Edward then marched south to blockade Gaston in his strongest castle:

“Edward marched in great power with his army into Gaston's lands, forced him to flee, and besieged him in the strong and well-defended castle to which he had retreated.”

- William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

The castle in question was probably the Château Moncade, a castle and fortified bourg that Gaston had only started to build in 1242; ironically, with money granted by Henry III. Only part of the keep remains today, but it was quite impressive at the time (see pics).

Gaston’s brief revolt had collapsed into the dust. On 14 January 1274 he agreed to surrender via the mediation of a papal envoy, though the envoy could do no more than facilitate Gaston’s complete submission to the king’s will.

Thanks to Rich Price, as ever, for the various translations.

Saturday, 18 January 2020

Philip's nose

Limoges and Béarn (4)

In late October 1273 the king of France, Philippe le Hardi - who apparently had a very long nose - ordered everyone in Limoges to stop fighting and appear before him for judgement at Saint-Martin.

The text of Philip’s sentence was only discovered in the late 19th century. He ordered the king of England to surrender the oath of fidelity he had received from the bourgeois; if he neglected to do this, the seneschal of Périgord would force him. Philip also instructed Edward to abstain from fighting the Viscomtesse of Limoges, who would remain in possession of the town. A second letter was sent to Edward, this time a personal message, in which the French king told his cousin to remove his bailiff from Limoges and to recognise the right of Marguerite to armed justice in the event of rebellion.

In short, Edward was told to get the hell out. The English king was a long way to the south, embroiled in his dispute with Gaston de Béarn. For the moment he ignored Philip and got on with the business in hand. He persuaded the court of Gascony to provide testimony that Gaston had been summoned to appear before the king on three successive occasions. The culprit refused all three, so Edward was empowered to move against him.

On 11 November the assembly gave Edward the go-ahead for military action. This was very similar to the conflict with Prince Llywelyn of Wales a couple of years later, when the king gained parliamentary approval for war after Llywellyn had refused five separate summons.

Edward marched into Marson and Gabardan, where all resistance collapsed after barely a fortnight. On 27 November Gaston’s daughter Constance came before the king and offered to yield up her father’s castles. She also forced the mayor and commune of Mont-de-Marsan to submit to Edward; the grovelling terms they offered are recorded in Gaston Register A.

See translation of the text below: