Today is the anniversary of the execution of Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, at Tyburn in 1330. At his trial Mortimer was gagged and thus unable to respond to the various charges of treason laid against him. Tellingly, this included the charge that he had 'accroached the royal power'. In the days before his execution Mortimer and two of his sons were walled up inside a chamber with no doors or windows next to the bedroom of the young Edward III, who had led the coup to overthrow his mother's ally and (possible) lover.

It is my belief - not necessarily shared by everyone - that Mortimer's failed bid for power was all part of his family's desire to seize the crowns of England and Wales in the past two generations: his father Edmund and uncle Roger had connived to murder Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales in 1282, an action clouded by the stubborn popular belief that Edward I organised the killing. It is clear from the private correspondence between the king, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn's death that they knew nothing of the affair, and were themselves threatened by it. Or at least that is what I glean from the surviving letters.

Edmund spent the rest of his days under a cloud of royal displeasure, but his son would murder two of Edward I's children - Edward II and the Earl of Kent - and come within an ace of toppling the grandson. In the event he failed and ended his days with a suitably dramatic flourish, leaping from the high scaffold at Tyburn in the black tunic he had worn at Edward II's funeral: a final 'up yours' to everyone. The snapping of his neck spelled the end of Mortimer power-grabs, at least for a generation or two.

Friday, 29 November 2019

Lacy's war

In January 1296 the English expeditionary force to Gascony finally got underway, seventeen months over schedule. This was originally supposed to be the second of a tripartite expedition in autumn 1294, planned to hit the French army of occupation with three successive waves of attack in the space of just nine weeks. The war of Prince Madog in Wales obliged Edward I to turn his resources against the Welsh instead, which meant the French in Gascony had time to prepare.

The leaders of the expedition were the king’s brother, Edmund of Lancaster, and Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. Edmund was in poor health but may have felt obliged to go: it was thanks to his botched diplomacy that the French had seized Gascony in the first place. The surrender on his orders to the constable of France, Raoul de Nesle, in March 1294 had included the handing over of most of the military strongholds in the duchy and the capital city, Bordeaux. Twenty ducal officers were also given up as hostages.

This meant that the English had voluntarily removed their own shield against French aggression, while the arrest of key members of the ducal administration left scarcely anyone to organise local resistance. The only bright spot was the enduring loyalty of the Gascons to the Plantagenet king-duke: of the 100 Gascon nobles summoned to arms by Edward I, about 80 answered the call. Those who defected to the French, lured by bribes or coercion, were mostly from the Agenais. This was a strip of territory located to the north of Gascony, only acquired by the English in 1279. Thus the inhabitants may have felt they owed their homage to the Capets instead of the Plantagenets.

Apart from the nobles, about 500 of the lesser Gascon gentry also stayed loyal to the English. Many of these chose exile in England rather than submission to the French, which meant they had to be provided for. Refugees from all over the duchy flocked to England, and the king was hard-put to find money and employment for them all. Gascon nobles queued up at the exchequer at York and Westminster to recieve funds. Edward paid them when he could, though usually in arrears: in June 1302, for instance, a cart loaded with the massive sum of £1000 was sent down from York to Westminster to pay Gascon creditors still not fully satisfied for their wages.

With much of Gascony in French hands, and so many loyal Gascons in England, Edmund and Lacy’s task was not an enviable one. They sailed for the north of the duchy, to try and re-establish a northern bridgehead against the French.

The map of Gascony is drawn by a friend of mine, Martin Bolton.

The leaders of the expedition were the king’s brother, Edmund of Lancaster, and Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. Edmund was in poor health but may have felt obliged to go: it was thanks to his botched diplomacy that the French had seized Gascony in the first place. The surrender on his orders to the constable of France, Raoul de Nesle, in March 1294 had included the handing over of most of the military strongholds in the duchy and the capital city, Bordeaux. Twenty ducal officers were also given up as hostages.

This meant that the English had voluntarily removed their own shield against French aggression, while the arrest of key members of the ducal administration left scarcely anyone to organise local resistance. The only bright spot was the enduring loyalty of the Gascons to the Plantagenet king-duke: of the 100 Gascon nobles summoned to arms by Edward I, about 80 answered the call. Those who defected to the French, lured by bribes or coercion, were mostly from the Agenais. This was a strip of territory located to the north of Gascony, only acquired by the English in 1279. Thus the inhabitants may have felt they owed their homage to the Capets instead of the Plantagenets.

Apart from the nobles, about 500 of the lesser Gascon gentry also stayed loyal to the English. Many of these chose exile in England rather than submission to the French, which meant they had to be provided for. Refugees from all over the duchy flocked to England, and the king was hard-put to find money and employment for them all. Gascon nobles queued up at the exchequer at York and Westminster to recieve funds. Edward paid them when he could, though usually in arrears: in June 1302, for instance, a cart loaded with the massive sum of £1000 was sent down from York to Westminster to pay Gascon creditors still not fully satisfied for their wages.

With much of Gascony in French hands, and so many loyal Gascons in England, Edmund and Lacy’s task was not an enviable one. They sailed for the north of the duchy, to try and re-establish a northern bridgehead against the French.

The map of Gascony is drawn by a friend of mine, Martin Bolton.

Wednesday, 27 November 2019

Murky Mortimers

A charter dated 1 May 1281, in which the abbot of Tal-y-Llychau pledged the abbey’s lands of Brechfa in Gothi and and the land of Brechfa except for Llanegwad to Rhys ap Maredudd for eighteen years.

The first name on the witness list to the charter is Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, the only ‘Englishman’ among the otherwise Welsh names. The Anglicised form of Mortimer’s name is deceptive: he was a grandson of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and a nephew of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, as well as third cousin to Rhys ap Maredudd and first cousin to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Mortimer involved himself deeply in the affairs of Pura Wallia at this time. A few months later, on 9 October, he met Prince Llywelyn at Mortimer’s castle at Radnor and entered into a ‘peace treaty and unbreakable agreement’ with his kinsman and old rival. This was probably on Llywelyn’s instigation and meant to secure Mortimer’s support against Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. Or was there more to it?

Llywelyn was the son of Gruffydd, whom Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had barred from the succession to Gwynedd on the grounds that he was the son of a ‘slave girl’; this was so Prince Llywelyn could put aside his first wife and marry Joan Plantagenet, daughter of King John. Roger Mortimer, on the other hand, was the grandson of the illegitimate but legitimised Princess Joan, which meant he had the blood of the English and Welsh royal families in his veins.

Roger was also the eldest surviving direct heir of his uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had deliberately excluded Grufydd and his brothers from the succession while Prince Dafydd and his bodily heirs lived. Dafydd had died in 1246 without an heir, but he left six uterine sisters. All but one of these had male heirs, of which Mortimer was the eldest. Under Welsh law it was technically impossible for a female to inherit land, but it was not impossible for a member of a royal family to stake a claim through the female line.

There is also the question of how Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rose to power in Gwynedd in the first place. There was no ‘coronation ceremony’ in 1246: instead Llywelyn and his brother Owain Goch seized power after the death of Prince Dafydd. Since they were both sons of a man who had been declared a bastard by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, neither had any automatic right to inherit.

This may explain why Llywelyn had no male heirs of his body, and made efforts to mend fences with Mortimer in 1281. Did Llywelyn intend to hand the crown of Wales over to his cousin Mortimer? His brother Dafydd was an outcast at this point, while Owain was in prison and Rhodri had sold off his rights to the principality.

Prince Rosser ap Ralf ap Llywelyn of Wales?

The first name on the witness list to the charter is Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, the only ‘Englishman’ among the otherwise Welsh names. The Anglicised form of Mortimer’s name is deceptive: he was a grandson of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and a nephew of Dafydd ap Llywelyn, as well as third cousin to Rhys ap Maredudd and first cousin to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Mortimer involved himself deeply in the affairs of Pura Wallia at this time. A few months later, on 9 October, he met Prince Llywelyn at Mortimer’s castle at Radnor and entered into a ‘peace treaty and unbreakable agreement’ with his kinsman and old rival. This was probably on Llywelyn’s instigation and meant to secure Mortimer’s support against Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. Or was there more to it?

Llywelyn was the son of Gruffydd, whom Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had barred from the succession to Gwynedd on the grounds that he was the son of a ‘slave girl’; this was so Prince Llywelyn could put aside his first wife and marry Joan Plantagenet, daughter of King John. Roger Mortimer, on the other hand, was the grandson of the illegitimate but legitimised Princess Joan, which meant he had the blood of the English and Welsh royal families in his veins.

Roger was also the eldest surviving direct heir of his uncle, Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth had deliberately excluded Grufydd and his brothers from the succession while Prince Dafydd and his bodily heirs lived. Dafydd had died in 1246 without an heir, but he left six uterine sisters. All but one of these had male heirs, of which Mortimer was the eldest. Under Welsh law it was technically impossible for a female to inherit land, but it was not impossible for a member of a royal family to stake a claim through the female line.

There is also the question of how Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rose to power in Gwynedd in the first place. There was no ‘coronation ceremony’ in 1246: instead Llywelyn and his brother Owain Goch seized power after the death of Prince Dafydd. Since they were both sons of a man who had been declared a bastard by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, neither had any automatic right to inherit.

This may explain why Llywelyn had no male heirs of his body, and made efforts to mend fences with Mortimer in 1281. Did Llywelyn intend to hand the crown of Wales over to his cousin Mortimer? His brother Dafydd was an outcast at this point, while Owain was in prison and Rhodri had sold off his rights to the principality.

Prince Rosser ap Ralf ap Llywelyn of Wales?

Monday, 25 November 2019

Statute of Wales (first draft)

The first draft of the Statute of Wales, photographed by me at the National Archives last week. This is an earlier, separate document to the official version of the statute that was declared at Rhuddlan in 1284. The burnt edges suggest it suffered during a great fire that destroyed many documents in 1731, and the content is different in some respects to the final version of Rhuddlan.

First, the draft shows that Edward I originally contemplated forming four shires in Gwynedd (‘in Snowdon’), with a sheriff of Aberconwy to administer the cantreds of Arllechwedd and Arfon and the commote of Creuddyn; a sheriff of Criccieth to superintend the cantreds of Lleyn and Dunoding; a sheriff of Merioneth, under whom would be the cantred of Merioneth and the commotes of Penllyn and Edeirnion; and a sheriff of Anglesey, who had the whole island under his charge. This arrangement was never carried out in practice.

Second, this early version is almost entirely concerned with the legal aspects of the new administration in Wales, but has not a word to say about the central administrative machinery or how the finances were to operate. According to RR Davies in his book ‘Age of Conquest’, this first draft also refers to the civil aspects of Welsh law being retained at the request of the people of Wales; the allusions to consent, however, were struck out from the final version. I personally could see none of this when I took a squint at the document, and it isn’t mentioned in other academic studies of the draft.

First, the draft shows that Edward I originally contemplated forming four shires in Gwynedd (‘in Snowdon’), with a sheriff of Aberconwy to administer the cantreds of Arllechwedd and Arfon and the commote of Creuddyn; a sheriff of Criccieth to superintend the cantreds of Lleyn and Dunoding; a sheriff of Merioneth, under whom would be the cantred of Merioneth and the commotes of Penllyn and Edeirnion; and a sheriff of Anglesey, who had the whole island under his charge. This arrangement was never carried out in practice.

Second, this early version is almost entirely concerned with the legal aspects of the new administration in Wales, but has not a word to say about the central administrative machinery or how the finances were to operate. According to RR Davies in his book ‘Age of Conquest’, this first draft also refers to the civil aspects of Welsh law being retained at the request of the people of Wales; the allusions to consent, however, were struck out from the final version. I personally could see none of this when I took a squint at the document, and it isn’t mentioned in other academic studies of the draft.

Sunday, 24 November 2019

The saga of Iorwerth Foel (2)

After his desertion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1278, Iorwerth drops out of sight for the next twenty years. He re-emerges in 1298 as a centenar (mounted officer) in charge of the footsoldiers of Anglesey between November 1297-November 1298. Iorwerth shared his command with three other centenars: Dafydd Foel (possibly a relative), Tudur Ddu - “Black Tudor” - and William Thloyt or Lloyd. The relevant muster roll is attached below.

These men were among the infantry of North Wales raised over the winter of 1297-8 to defend the northern counties of England against Sir William Wallace. Of the 30,000 men of Wales and England summoned to defend the north, only those raised from Anglesey and Snowdon came near to filling their quota: 2000 were summoned and 1939 actually showed up, which was extremely unusual for this campaign.

This meant that Edward I had two Welsh armies in the field at the same time: 6213 archers under his personal command in Flanders, and a total of 5157 in northern England under the command of Earl Warenne. The captain of the Welsh contingent, Gruffudd Llwyd, served under Warenne from 8 December 1297 to 29 January 1298, and was then sent to Flanders from January to March.

Gruffudd was not present at the Battle of Falkirk, fought on 22 August 1298. Iorwerth’s term of service covers the time of the battle, so he may have been present on the killing fields:

“And so the Welsh were held back from attacking the Scots, until the King triumphed and the Scots fell everywhere, like the flowers of the forest as the fruit grows. Then said the King, "If the Lord be with us, who shall be against us?" The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the field, like the snow in winter.” -

William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

These men were among the infantry of North Wales raised over the winter of 1297-8 to defend the northern counties of England against Sir William Wallace. Of the 30,000 men of Wales and England summoned to defend the north, only those raised from Anglesey and Snowdon came near to filling their quota: 2000 were summoned and 1939 actually showed up, which was extremely unusual for this campaign.

This meant that Edward I had two Welsh armies in the field at the same time: 6213 archers under his personal command in Flanders, and a total of 5157 in northern England under the command of Earl Warenne. The captain of the Welsh contingent, Gruffudd Llwyd, served under Warenne from 8 December 1297 to 29 January 1298, and was then sent to Flanders from January to March.

Gruffudd was not present at the Battle of Falkirk, fought on 22 August 1298. Iorwerth’s term of service covers the time of the battle, so he may have been present on the killing fields:

“And so the Welsh were held back from attacking the Scots, until the King triumphed and the Scots fell everywhere, like the flowers of the forest as the fruit grows. Then said the King, "If the Lord be with us, who shall be against us?" The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the field, like the snow in winter.” -

William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

The saga of Iorwerth Foel (1)

Iorwerth Foel was a landholder of Anglesey in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century. His great-great granddaughter was Margaret Hanmer, wife of Owain Glyn Dwr.

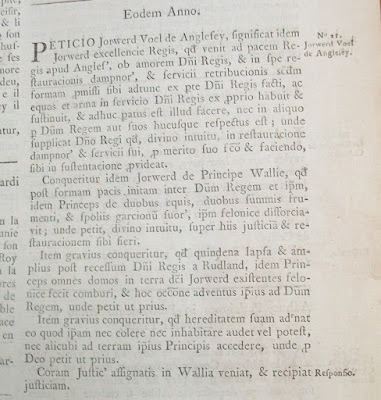

In 1278 Iorwerth presented a petition to parliament (above), complaining that when he had come to the King’s peace and then served the King in war, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had taken his horses and corn, and the plunder of his men, and therefore Iorwerth claimed justice and restitution. Llywelyn had done these things after the peace of Aberconwy, and hence was guilty of felony. Iorwerth also complained that a fortnight or more after the departure of the King from Rhuddlan, Prince Llywelyn had feloniously burnt all the houses on his land, on account of Iorwerth joining the King’s army. Lastly, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the Prince. On these complaints he was told to go before the Justices assigned in Wales and receive justice. The final outcome of the plea is unknown.

Prince Llywelyn’s treatment of Iorwerth either suggests he had a short way with dissenters, or was particularly outraged at the defection of one of his closest supporters at a crucial time:

“This case was just one of many which showed that Llywelyn could no longer rely on the support of his own subjects, let alone on that of leading Welshmen outside Gwynedd.” - AD Carr, Medieval Anglesey

In 1278 Iorwerth presented a petition to parliament (above), complaining that when he had come to the King’s peace and then served the King in war, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had taken his horses and corn, and the plunder of his men, and therefore Iorwerth claimed justice and restitution. Llywelyn had done these things after the peace of Aberconwy, and hence was guilty of felony. Iorwerth also complained that a fortnight or more after the departure of the King from Rhuddlan, Prince Llywelyn had feloniously burnt all the houses on his land, on account of Iorwerth joining the King’s army. Lastly, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the Prince. On these complaints he was told to go before the Justices assigned in Wales and receive justice. The final outcome of the plea is unknown.

Prince Llywelyn’s treatment of Iorwerth either suggests he had a short way with dissenters, or was particularly outraged at the defection of one of his closest supporters at a crucial time:

“This case was just one of many which showed that Llywelyn could no longer rely on the support of his own subjects, let alone on that of leading Welshmen outside Gwynedd.” - AD Carr, Medieval Anglesey

Saturday, 16 November 2019

Legal fictions

Serving two masters (6, and last)

The death of the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd in the war of 1282, fighting on opposite sides, left their heirs vulnerable to rival claimants. In about 1307 Rhys’s son, Gruffudd Llwyd, moved to secure his inheritance from Thomas Bek, the predatory Bishop of St David’s. Gruffydd wrote to the council in London and reminded them that:

“His uncle, Hywel ap Gruffudd, knight…died in the service of the king, the father of our king, at the bridge of Anglesey, in the company of Sir Otto Grandison in the war of Llywelyn and Dafydd.”

This was true enough, but Gruffudd went further and claimed that: “After the conquest, the said Rhys ap Gruffydd, his brother and father of this Gruffudd [meaning himself], was assigned by the king as guardian of the county of Caernarfon and sworn to his council and in this state he died, as the earl of Lincoln, the said Sir Otto and other great lords of the king’s council can testify.”

Thus Gruffudd claimed that his father was not killed with Prince Llywelyn at Cilmeri, as the Peterborough chronicler claimed, but survived and was taken back into royal service. Gruffudd’s statement is flatly contradicted by the records. On 20 April 1284 the king allowed Margaret, the wife of Rhys ap Gruffudd, her lordship of Tregarnedd in Anglesey for life. Edward was not happy about the grant, which he regarded as neither “stable or firm”, but it was made over anyway. A few days later, on 4 May, the earl of Lincoln was ordered to deliver Rhys’s lands in the cantref of Rhos over to his son, Gruffudd.

If Rhys was still alive, than neither of the above grants make any sense. He was dead by 20 May 1284 at the latest and almost certainly died at Cilmeri in December 1282. Gruffudd’s claim that his father was made ‘guardian of the county of Caernarfon’ is also bogus, for the shire was not even formed until 3 March 1284, fourteen months after the last possible date his father may have been alive. The only other possibility is that Edward I made Rhys guardian for Caernarfonshire and then forgot to tell anyone, which doesn’t seem likely.

Therefore Gruffudd Llwyd - later Sir Gruffudd Llwyd - tried to persuade Edward II that his father, Rhys, was loyal to Edward I until the end. This legal subterfuge was probably employed to protect Gruffudd’s standing in the edgy conditions of postconquest Wales. With regard to the actual petition, Gruffudd sold his advowson to the church of Llanrhystyd to the Bishop of St David’s in 1309, but held onto the rest of his lands. These were inherited by his son, Ieuan, Justice of South Wales, on 28 August 1335.

The death of the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd in the war of 1282, fighting on opposite sides, left their heirs vulnerable to rival claimants. In about 1307 Rhys’s son, Gruffudd Llwyd, moved to secure his inheritance from Thomas Bek, the predatory Bishop of St David’s. Gruffydd wrote to the council in London and reminded them that:

“His uncle, Hywel ap Gruffudd, knight…died in the service of the king, the father of our king, at the bridge of Anglesey, in the company of Sir Otto Grandison in the war of Llywelyn and Dafydd.”

This was true enough, but Gruffudd went further and claimed that: “After the conquest, the said Rhys ap Gruffydd, his brother and father of this Gruffudd [meaning himself], was assigned by the king as guardian of the county of Caernarfon and sworn to his council and in this state he died, as the earl of Lincoln, the said Sir Otto and other great lords of the king’s council can testify.”

Thus Gruffudd claimed that his father was not killed with Prince Llywelyn at Cilmeri, as the Peterborough chronicler claimed, but survived and was taken back into royal service. Gruffudd’s statement is flatly contradicted by the records. On 20 April 1284 the king allowed Margaret, the wife of Rhys ap Gruffudd, her lordship of Tregarnedd in Anglesey for life. Edward was not happy about the grant, which he regarded as neither “stable or firm”, but it was made over anyway. A few days later, on 4 May, the earl of Lincoln was ordered to deliver Rhys’s lands in the cantref of Rhos over to his son, Gruffudd.

If Rhys was still alive, than neither of the above grants make any sense. He was dead by 20 May 1284 at the latest and almost certainly died at Cilmeri in December 1282. Gruffudd’s claim that his father was made ‘guardian of the county of Caernarfon’ is also bogus, for the shire was not even formed until 3 March 1284, fourteen months after the last possible date his father may have been alive. The only other possibility is that Edward I made Rhys guardian for Caernarfonshire and then forgot to tell anyone, which doesn’t seem likely.

Therefore Gruffudd Llwyd - later Sir Gruffudd Llwyd - tried to persuade Edward II that his father, Rhys, was loyal to Edward I until the end. This legal subterfuge was probably employed to protect Gruffudd’s standing in the edgy conditions of postconquest Wales. With regard to the actual petition, Gruffudd sold his advowson to the church of Llanrhystyd to the Bishop of St David’s in 1309, but held onto the rest of his lands. These were inherited by his son, Ieuan, Justice of South Wales, on 28 August 1335.

Friday, 15 November 2019

Brothers in death

Serving two masters (5)

On 8 December 1281, at Aberffraw, Rhys ap Gruffudd was fined £100 by Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as a punishment for his ‘disobedience and contempt’. No further details are supplied, so we are left to speculate as to the nature of Rhys’s offence.

On 30 December, at Beddgelert, a new arrangement was made between Prince Llywelyn and Rhys. This would suggest tempers had cooled, and the two men settled their disagreement. Rhys, once Llywelyn’s bailiff, had been in English service since 1276. Now he went back to his former master.

The next winter, 6 November 1282, Rhys’s brother Hywel was drowned at the Battle of the Bridge of Boats on the Menai strait. Hywel had remained a crown loyalist and was put in command of the English fleet on Anglesey:

“And King Edward of England sent a fleet of ships to Anglesey, with Hywel ap Gruffudd ab Ednyfed as leader at their head; and they gained possession of Anglesey. And they desired to gain possession of Arfon. And then was made the bridge over the Menai; but the bridge broke under an excessive load, and countless numbers of the English were drowned, and others were slain”.

- Brut y Tywysogion

Rhys’s feelings, on hearing this news, can only be imagined. Over a month later he joined his brother in death. On 10/11 December, near Cilmeri, Rhys fell beside Prince Llywelyn:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of his land who died with him; namely ‘Almafan’ who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield.”

- Chronicle of Peterborough

On 8 December 1281, at Aberffraw, Rhys ap Gruffudd was fined £100 by Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd as a punishment for his ‘disobedience and contempt’. No further details are supplied, so we are left to speculate as to the nature of Rhys’s offence.

On 30 December, at Beddgelert, a new arrangement was made between Prince Llywelyn and Rhys. This would suggest tempers had cooled, and the two men settled their disagreement. Rhys, once Llywelyn’s bailiff, had been in English service since 1276. Now he went back to his former master.

The next winter, 6 November 1282, Rhys’s brother Hywel was drowned at the Battle of the Bridge of Boats on the Menai strait. Hywel had remained a crown loyalist and was put in command of the English fleet on Anglesey:

“And King Edward of England sent a fleet of ships to Anglesey, with Hywel ap Gruffudd ab Ednyfed as leader at their head; and they gained possession of Anglesey. And they desired to gain possession of Arfon. And then was made the bridge over the Menai; but the bridge broke under an excessive load, and countless numbers of the English were drowned, and others were slain”.

- Brut y Tywysogion

Rhys’s feelings, on hearing this news, can only be imagined. Over a month later he joined his brother in death. On 10/11 December, near Cilmeri, Rhys fell beside Prince Llywelyn:

“Furthermore, not one of the prince’s cavalry escaped death, but they were killed with 3000 of the foot and also the three magnates of his land who died with him; namely ‘Almafan’ who was lord of Llanbadarn Fawr, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who was seneschal of all the land of the prince, and thirdly, it is thought, Llywelyn Fychan, who was lord of Bromfield.”

- Chronicle of Peterborough

Paying suit

Serving two masters (4)

In 1279 the brothers Rhys and Hywel ap Gruffudd lost their lands in Wales. On 8 November the king ordered Hywel ap Maredudd (one of Rhys’s colleagues on the commission to govern Wales) and John Perres to inquire into the rights of the brothers in Caeo, a commote of Cantref Mawr, which they had been unjustly ‘diseissed’ (deprived) of by Rhys ap Maredudd.

This case gives an idea of the chaotic rivalry that existed between the descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth. Rhys and Hywel were both descended from Lord Rhys via their grandfather’s marriage to his daughter, Gwenllian. Caeo itself was held by Rhys Wyndod, lord of Dinefwr and another descendant. The commote was claimed by Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Dryslwyn and yet another descendant. Presumably this means that the brothers held their part of Caeo from Rhys Wyndod as chief lord.

Rhys ap Maredudd’s specific complaint was that Hywel ap Maredudd refused to pay suit at Rhys’s court of Llansadwrn. To owe suit required a man to attend a specific court and pay a fee to have his cases heard; Rhys was thus concerned with the loss of prestige and revenue if Hywel was allowed to detach himself from the lord of Dryslwyn’s jurisdiction.

To pay suit was a part of English common law, and Rhys asked the king to have a writ to the royal bailiffs at Dinefwr to distrain Hywel and force him to pay suit, ‘as he was accustomed to do in the time of the father of Rhys’. This all gave rise to an awkward situation in which one of the team of four Welsh justices appointed to govern Wales and the Marches was himself a sub-tenant of a regional lord of Cantref Mawr. This man and his brother also apparently owed legal services to a neighbouring lord of Cantref Mawr, who refused to acknowledge his cousin’s authority in Caeo and did his best to muscle in on the territory. Unfortunately the outcome of the case is unknown.

Caeo itself was a fairly important trading centre. A survey of 1303-4 discovered that the hamlet of Cynwil inside Caeo was home to eight ‘chensers’ or censarii, who paid for the privilege of buying and selling freely within the town in weekly markets and annual fairs. The presence of a market at Cynwil is indicated by the collection of petty tolls from people passing through the hamlet. A percentage of these fees and tolls would have been creamed off by the local bigwigs, which might explain why they were all squabbling over possession of the commote.

This case gives an idea of the chaotic rivalry that existed between the descendants of the Lord Rhys of Deheubarth. Rhys and Hywel were both descended from Lord Rhys via their grandfather’s marriage to his daughter, Gwenllian. Caeo itself was held by Rhys Wyndod, lord of Dinefwr and another descendant. The commote was claimed by Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Dryslwyn and yet another descendant. Presumably this means that the brothers held their part of Caeo from Rhys Wyndod as chief lord.

Rhys ap Maredudd’s specific complaint was that Hywel ap Maredudd refused to pay suit at Rhys’s court of Llansadwrn. To owe suit required a man to attend a specific court and pay a fee to have his cases heard; Rhys was thus concerned with the loss of prestige and revenue if Hywel was allowed to detach himself from the lord of Dryslwyn’s jurisdiction.

To pay suit was a part of English common law, and Rhys asked the king to have a writ to the royal bailiffs at Dinefwr to distrain Hywel and force him to pay suit, ‘as he was accustomed to do in the time of the father of Rhys’. This all gave rise to an awkward situation in which one of the team of four Welsh justices appointed to govern Wales and the Marches was himself a sub-tenant of a regional lord of Cantref Mawr. This man and his brother also apparently owed legal services to a neighbouring lord of Cantref Mawr, who refused to acknowledge his cousin’s authority in Caeo and did his best to muscle in on the territory. Unfortunately the outcome of the case is unknown.

Caeo itself was a fairly important trading centre. A survey of 1303-4 discovered that the hamlet of Cynwil inside Caeo was home to eight ‘chensers’ or censarii, who paid for the privilege of buying and selling freely within the town in weekly markets and annual fairs. The presence of a market at Cynwil is indicated by the collection of petty tolls from people passing through the hamlet. A percentage of these fees and tolls would have been creamed off by the local bigwigs, which might explain why they were all squabbling over possession of the commote.

Thursday, 14 November 2019

Divide and rule

Serving two masters (3)

Via the Treaty of Aberconwy, 9 November 1277, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was required to release his vassal Rhys ap Gruffudd from prison:

“That Llywelyn should free Rhys ap Gruffudd and restore him to the state he occupied when he first came to the lord king and was brought into his peace.”

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales.

The make-up of the commission reveals Edward I’s notions of how Wales would be governed post-Aberconwy. His idea was to build up a ministerial elite of loyalist Welshmen who would work alongside a roughly equal number of English officials to administer Wales on the king’s behalf. He would later attempt to do something very similar in Scotland, with an equal number of Scots and Englishmen appointed as councillors and sheriffs.

In Wales these ministers were drawn from the uchelwyr - the landholding class below the rank of prince - and the Welsh church. This was at the expense of the princes, not least Llywelyn himself. There was an element of divide and rule here: by promoting the uchelwyr over the princes, the king created a base of native support in Wales while ensuring that the two classes were opposed to each other. In a move that would have shocked Prince Llywelyn, on 10 January 1278 Edward ordered him to appear before the new commission:

“The king has ordered Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales to be before them in those parts to propound the suits of himself and his men and to do and receive jusice”.

The members of this commission were Rhys ap Gruffudd, Archdeacon Maredudd of Cardigan, Hywel ap Maredudd and Goronwy ap Heilyn. All four had once been Llywelyn’s vassals, and now he was required to appear before them as his judges. Perhaps to reconcile Llywelyn, in June the king ordered that the remit of the commission should be widened to cover the English counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire. Thus a team of Welsh justices were given effective jurisdiction over Wales and a big chunk of western England.

On 20 June 1278 Edward went further, and ordered that the four Welshmen on the team of seven should be given exclusive rights to hear and determine all pleas in Wales and the Marches. The English head of the commission, Walter of Hopton, was required to take their oath in his place. This act shows the extraordinary faith Edward placed in the Welshmen on the commission, two of which had been in rebellion against him within the past year.

“That Llywelyn should free Rhys ap Gruffudd and restore him to the state he occupied when he first came to the lord king and was brought into his peace.”

The clauses of the treaty also required Llywelyn to release Owain ap Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, Dafydd ap Gruffudd ab Owain and his cousin Elise ab Iorwerth, as well as Madog ap Einion. In the next year Rhys ap Gruffudd was serving in the king’s household at a knight’s wage of two shillings a day up until Michaelmas. A month before this, on 18 January 1278, he had been appointed the last member of the judicial branch of three Englishmen and four Welshmen on the Hopton Commission, set up to deal with land claims in Wales.

The make-up of the commission reveals Edward I’s notions of how Wales would be governed post-Aberconwy. His idea was to build up a ministerial elite of loyalist Welshmen who would work alongside a roughly equal number of English officials to administer Wales on the king’s behalf. He would later attempt to do something very similar in Scotland, with an equal number of Scots and Englishmen appointed as councillors and sheriffs.

In Wales these ministers were drawn from the uchelwyr - the landholding class below the rank of prince - and the Welsh church. This was at the expense of the princes, not least Llywelyn himself. There was an element of divide and rule here: by promoting the uchelwyr over the princes, the king created a base of native support in Wales while ensuring that the two classes were opposed to each other. In a move that would have shocked Prince Llywelyn, on 10 January 1278 Edward ordered him to appear before the new commission:

“The king has ordered Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd of Wales to be before them in those parts to propound the suits of himself and his men and to do and receive jusice”.

The members of this commission were Rhys ap Gruffudd, Archdeacon Maredudd of Cardigan, Hywel ap Maredudd and Goronwy ap Heilyn. All four had once been Llywelyn’s vassals, and now he was required to appear before them as his judges. Perhaps to reconcile Llywelyn, in June the king ordered that the remit of the commission should be widened to cover the English counties of Herefordshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire. Thus a team of Welsh justices were given effective jurisdiction over Wales and a big chunk of western England.

On 20 June 1278 Edward went further, and ordered that the four Welshmen on the team of seven should be given exclusive rights to hear and determine all pleas in Wales and the Marches. The English head of the commission, Walter of Hopton, was required to take their oath in his place. This act shows the extraordinary faith Edward placed in the Welshmen on the commission, two of which had been in rebellion against him within the past year.

Wednesday, 13 November 2019

Preachers and plots

Serving two masters (2)

In the summer of 1277 a plot was hatched against Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd by the Dominican brothers of the Order of Preachers. The evidence of this plot is contained in a document (attached) witnessed at Chester on 21 July, in which Friar Llywelyn testifies to his mediation between Edward I on the one part, and on the other, the friar’s uterine brother Rhys ap Gruffudd and his kinsmen, Hywel ap Goronwy and Gruffudd ap Iorwerth.

Rhys, Hywel and Goronwy had earlier received the king’s permission to negotiate terms with any royal officer of their choice. This instruction was issued on 22 May, two months before Friar Llywelyn interceded on their behalf. In the document dated 21 July, the friar advises Rhys and his kinsmen to make their peace with the king and do homage. He assures them that the king would grant them their lands and rights and that, pending the recovery of their lands, they would be provided for.

The Welsh Dominicans were instrumental in the negotiations between the king and Prince Llywelyn at this time. Friar Llywelyn can most likely be identified with the Friar Llywelyn of Bangor who, along with Prior Ifor of Rhuddlan, received oaths for the observance of the Treaty of Aberconwy after Prince Llywelyn’s surrender in November. Rhys ap Gruffudd, as noted in my previous post, was one of Llywelyn’s chief counsellors. In May-July 1277 he was evidently seeking favourable terms from the king, and to disassociate himself from Llywelyn. He was too slow to act, and Llywelyn seized and imprisoned him before Rhys could escape into England. By the terms of Aberconwy, dated 9 November, Llywelyn was obliged to release Rhys and restore him to the status he had held when he first negotiated with the king.

Another of the men named on the document, Gruffudd ap Iorwerth, can probably be identified with Gruffudd ap Iorwerth ap Maredudd of Anglesey. In a letter written between the wars of 1277-82, Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd asked the king to restore Gruffudd to his lands in Anglesey, since he had committed no trespass. An elegy was later composed in Gruffudd’s honour by the Welsh bard, Bleddyn Fardd.

The four sons of Gruffudd remained crown loyalists. After the deposition of Edward II, they were named among the uchelwyr of Gwynedd who swore to restore the king to his throne. One of them - confusingly named Llywelyn ap Gruffudd - described himself to Edward II as ‘pencenedl’ or head of his kindred. Thus, the head of the lineage of Gruffudd ap Iorwerth was apparently named after the man their father had chosen to abandon.

The Welsh Dominicans were instrumental in the negotiations between the king and Prince Llywelyn at this time. Friar Llywelyn can most likely be identified with the Friar Llywelyn of Bangor who, along with Prior Ifor of Rhuddlan, received oaths for the observance of the Treaty of Aberconwy after Prince Llywelyn’s surrender in November. Rhys ap Gruffudd, as noted in my previous post, was one of Llywelyn’s chief counsellors. In May-July 1277 he was evidently seeking favourable terms from the king, and to disassociate himself from Llywelyn. He was too slow to act, and Llywelyn seized and imprisoned him before Rhys could escape into England. By the terms of Aberconwy, dated 9 November, Llywelyn was obliged to release Rhys and restore him to the status he had held when he first negotiated with the king.

Another of the men named on the document, Gruffudd ap Iorwerth, can probably be identified with Gruffudd ap Iorwerth ap Maredudd of Anglesey. In a letter written between the wars of 1277-82, Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd asked the king to restore Gruffudd to his lands in Anglesey, since he had committed no trespass. An elegy was later composed in Gruffudd’s honour by the Welsh bard, Bleddyn Fardd.

The four sons of Gruffudd remained crown loyalists. After the deposition of Edward II, they were named among the uchelwyr of Gwynedd who swore to restore the king to his throne. One of them - confusingly named Llywelyn ap Gruffudd - described himself to Edward II as ‘pencenedl’ or head of his kindred. Thus, the head of the lineage of Gruffudd ap Iorwerth was apparently named after the man their father had chosen to abandon.

Slanders and old poets

Serving two masters (1)

Rhys ap Gruffydd was one of the many grandsons of Ednyfed Fychan, seneschal or distain to Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. His father, Gruffydd, is traditionally supposed to have fled to Ireland as a result of a slander concerning Llywelyn’s wife, Joan Plantagenet. The alleged slander is contained in a book of pedigrees by John Tudor of the parish of St Asaph, described as an ‘old poet’. He died in 1602.

If true, it would appear Joan was the focus of a second scandal in Gwynedd after the more famous incident involving William de Braose. Gruffydd’s precise role in the ‘slander’ is not described, but he was obliged to stay in Ireland until Llywelyn died. This would imply he had done something the prince could not forgive.

His son, Rhys, was untainted by all this and became a long-term servant of Prince Llywelyn ap Guffudd. In 1272 he witnessed a document on his master’s behalf at Caernarfon and was later appointed as one of Llywelyn’s bailiffs of the Middle Marches. He was also present at the interrogation of Gruffudd ap Gwenwnwyn in 1274, after the latter’s alleged role in the notorious plot against Llywelyn’s life.

During the time of Llywelyn’s supremacy (1256-76) Rhys married Margaret, a daughter of the Marcher baron John Lestrange IV. Before 1276 John mortgaged his vill of Moreton in Shropshire to his son-in-law for 120 marks (£80). John repaid most of this sum in the form of a destrier worth eighty marks and a palfrey worth twenty.

In January 1277 the manor of Moreton was seized into the king’s hands after an inquisition found that it had been in the possession of Rhys; this can only mean that at first Rhys adhered to Prince Llywelyn in the war of 1276-77, and was disinherited as a result.

If true, it would appear Joan was the focus of a second scandal in Gwynedd after the more famous incident involving William de Braose. Gruffydd’s precise role in the ‘slander’ is not described, but he was obliged to stay in Ireland until Llywelyn died. This would imply he had done something the prince could not forgive.

His son, Rhys, was untainted by all this and became a long-term servant of Prince Llywelyn ap Guffudd. In 1272 he witnessed a document on his master’s behalf at Caernarfon and was later appointed as one of Llywelyn’s bailiffs of the Middle Marches. He was also present at the interrogation of Gruffudd ap Gwenwnwyn in 1274, after the latter’s alleged role in the notorious plot against Llywelyn’s life.

During the time of Llywelyn’s supremacy (1256-76) Rhys married Margaret, a daughter of the Marcher baron John Lestrange IV. Before 1276 John mortgaged his vill of Moreton in Shropshire to his son-in-law for 120 marks (£80). John repaid most of this sum in the form of a destrier worth eighty marks and a palfrey worth twenty.

In January 1277 the manor of Moreton was seized into the king’s hands after an inquisition found that it had been in the possession of Rhys; this can only mean that at first Rhys adhered to Prince Llywelyn in the war of 1276-77, and was disinherited as a result.

Monday, 11 November 2019

The king's right eye

In early 1302 French agents were supposed to arrive in Scotland, to take custody of all the lands Edward I had conquered in the southwest since the previous summer. The deadline for their arrival was “the fortnight after Candlemas” or 16 February.

The 16th of February passed without a Frenchman in sight. Edward, who had stopped at Roxburgh on his way south, was left secure in all the lands and castles in question. He quickly pressed his advantage and ordered Master James of St George, who had worked on the great chain of castles in Wales, to set out for Scotland.

Philip le Bel’s failure to send any men to Scotland exposed the emptiness of the Franco-Scots alliance. It had terrible consequences for the patriotic cause. Robert de Bruce had already defected to the English, convinced that Philip was about to send an army to restore John Balliol on the Scottish throne. Other Scottish knights, namely Simon Fraser and Herbert Morham, had left English service in the expectation of a permanent French alliance and final victory over Edward. Now they were left to face the wrath of the Plantagenet alone.

Why Philip made this decision is uncertain. Either he never meant to honour the agreement in the first place - which begs the question of why he bothered to implement it - or his circumstances had changed.

The answer probably lies in the talks that took place at Asnières in France between the English and French envoys. The English envoys were led by Walter Langton, a supremely able diplomat labelled “the king’s right eye in all matters” by Edward’s queen, Margaret of France. His counterpart on the French side was the no less able Pierre Flote, a brilliant lawyer and fanatical advocate of French expansionism.

Between them these two massive brains probably cooked up a cynical arrangement, whereby Philip agreed to dump the Scots if Edward dumped the Flemish. They could come to no agreement on the status of John Balliol, who was elegantly shoved aside. If Philip had gone ahead with his threat and sent Balliol back to Scotland, it is quite feasible a pitched battle would have taken place between Balliol and his supporter William Wallace on the one side, and Edward and Bruce on the other.

That could have been interesting.

|

| Philip le Bel |

The 16th of February passed without a Frenchman in sight. Edward, who had stopped at Roxburgh on his way south, was left secure in all the lands and castles in question. He quickly pressed his advantage and ordered Master James of St George, who had worked on the great chain of castles in Wales, to set out for Scotland.

Philip le Bel’s failure to send any men to Scotland exposed the emptiness of the Franco-Scots alliance. It had terrible consequences for the patriotic cause. Robert de Bruce had already defected to the English, convinced that Philip was about to send an army to restore John Balliol on the Scottish throne. Other Scottish knights, namely Simon Fraser and Herbert Morham, had left English service in the expectation of a permanent French alliance and final victory over Edward. Now they were left to face the wrath of the Plantagenet alone.

Why Philip made this decision is uncertain. Either he never meant to honour the agreement in the first place - which begs the question of why he bothered to implement it - or his circumstances had changed.

The answer probably lies in the talks that took place at Asnières in France between the English and French envoys. The English envoys were led by Walter Langton, a supremely able diplomat labelled “the king’s right eye in all matters” by Edward’s queen, Margaret of France. His counterpart on the French side was the no less able Pierre Flote, a brilliant lawyer and fanatical advocate of French expansionism.

Between them these two massive brains probably cooked up a cynical arrangement, whereby Philip agreed to dump the Scots if Edward dumped the Flemish. They could come to no agreement on the status of John Balliol, who was elegantly shoved aside. If Philip had gone ahead with his threat and sent Balliol back to Scotland, it is quite feasible a pitched battle would have taken place between Balliol and his supporter William Wallace on the one side, and Edward and Bruce on the other.

That could have been interesting.

Sunday, 10 November 2019

Pigs might soar

Sometime over the winter of 1301-2, probably over Christmas, Robert de Bruce submitted to the English. He did so for two reasons. Edward I had agreed to a truce with Philip le Bel, whereby all the castles and land conquered by the English in southwest Scotland would be handed over to French agents. This included Bruce’s castle at Turnberry, and he was not prepared to lose it to the French; technically Philip’s men were supposed to hand everything back when the truce expired, which was about as likely as pigs developing powers of aviation.

There was also the threat of John Balliol. Bruce wanted to be King of Scots, which he couldn’t be if Philip put Balliol back on the Scottish throne. What nobody realised - except possibly Edward’s spymaster, Walter Langton - is that Philip was bluffing. What he really wanted was to remove the threat of Edward sending any more troops to Flanders, and used Balliol and the Scots to that end.

Bruce first made contact with John de St John, Edward’s keeper of Galloway. St John was a relatively decent character for the era, and Bruce may have trusted the man not to play him false. After some cautious initial talks Bruce met with St John at Lochmaben, in the presence of ‘many good people’.

This stuff was too important to be conducted via a mediator, so Bruce probably went to meet Edward in person. They hadn’t seen each other for five years, and there were certain safeguards: the king had to guarantee that Bruce would not be harmed or lose his lands. In exchange Bruce made a show of contrition, though the reality was that both men needed something from each other. The terms they negotiated are vague on the most vital point. If Balliol returned to Scotland, and Edward’s ‘right’ (le droit) to rule the country was reversed - presumably by the pope - Edward would allow Bruce to pursue his ‘right’ in the English court. If the ‘right’ was pursued in some other court, Edward would provide assistance.

Whatever the hell this means has been disputed by historians. Possibly ‘le droit’ referred to the Bruce claim to the throne, which meant Edward promised to set Bruce up as a rival King of Scots to Balliol, with himself as Lord Paramount. Alternatively, the ‘right’ may have amounted to no more than Bruce’s family estates and the earldom of Carrick.

In any case, Bruce’s submission seems to have lifted the old king’s spirits. On 20 January 1302 Edward staged an Arthurian-themed ‘Round Table’ tournament at Falkirk, on the site of his defeat of William Wallace four years earlier. Possibly this was to celebrate Bruce’s return to the fold. Whether or not Bruce competed in the tourney, dressed up as one of King Arthur’s knights, is unknown.

There was also the threat of John Balliol. Bruce wanted to be King of Scots, which he couldn’t be if Philip put Balliol back on the Scottish throne. What nobody realised - except possibly Edward’s spymaster, Walter Langton - is that Philip was bluffing. What he really wanted was to remove the threat of Edward sending any more troops to Flanders, and used Balliol and the Scots to that end.

Bruce first made contact with John de St John, Edward’s keeper of Galloway. St John was a relatively decent character for the era, and Bruce may have trusted the man not to play him false. After some cautious initial talks Bruce met with St John at Lochmaben, in the presence of ‘many good people’.

This stuff was too important to be conducted via a mediator, so Bruce probably went to meet Edward in person. They hadn’t seen each other for five years, and there were certain safeguards: the king had to guarantee that Bruce would not be harmed or lose his lands. In exchange Bruce made a show of contrition, though the reality was that both men needed something from each other. The terms they negotiated are vague on the most vital point. If Balliol returned to Scotland, and Edward’s ‘right’ (le droit) to rule the country was reversed - presumably by the pope - Edward would allow Bruce to pursue his ‘right’ in the English court. If the ‘right’ was pursued in some other court, Edward would provide assistance.

Whatever the hell this means has been disputed by historians. Possibly ‘le droit’ referred to the Bruce claim to the throne, which meant Edward promised to set Bruce up as a rival King of Scots to Balliol, with himself as Lord Paramount. Alternatively, the ‘right’ may have amounted to no more than Bruce’s family estates and the earldom of Carrick.

In any case, Bruce’s submission seems to have lifted the old king’s spirits. On 20 January 1302 Edward staged an Arthurian-themed ‘Round Table’ tournament at Falkirk, on the site of his defeat of William Wallace four years earlier. Possibly this was to celebrate Bruce’s return to the fold. Whether or not Bruce competed in the tourney, dressed up as one of King Arthur’s knights, is unknown.

Broken covenants

In August 1301 the English campaign in Scotland ground to a halt, scuppered once again by lack of money and supplies. There were also diplomatic pressures to contend with. Philip le Bel chose this moment to throw his weight behind the Guardians, and sent envoys to treat with the English at Glasgow.

The terms discussed expose the weakness of Edward’s position in Scotland at this time. His envoys agreed to a truce with the Scots, to commence on 26 January 1302 and end on 1 November. For the duration of the truce all of the lands and castles which he had taken in southwest Scotland during the summer of 1301 would be placed in the custody of Philip’s agents. When the truce expired, they would be handed back to the English. The Scots, apparently, didn’t get a look-in.

Edward had been burned like this before. In the negotiations over Gascony in 1294, he had agreed to hand over key towns and castles to Philip, who would then return them after a grace period of forty days. Instead the French king simply broke his own covenant and confiscated the duchy.

Now it was happening all over again. Except it wasn’t. Edward wouldn’t fall for the same trick twice, and in the autumn of 1301 drew up new indentures for the supply of his garrisons in southwest Scotland. Massive purveyances of food were ordered from England and Ireland for the garrisons of Dumfries, Lochmaben and Ayr. This would not have happened if the English king meant to hand over his recent conquests to the French. Thus the peace talks at Glasgow were so much hot air: if Philip wanted those castles, he would have to send a French army to Scotland to take them.

Everyone, the Scots included, must have been aware of Philip’s past behaviour, and that there was zero chance he would honour the terms of any truce. He may have toyed with the idea of turning Scotland into a permanent outpost of France. This idea had been suggested to him by the English traitor, Thomas Turberville, in 1295. In a secret letter to the French king, Tuberville advised him to send men to Scotland:

"Wherefore I counsel you forthwith to send great persons into Scotland; for if you can enter therein, you will have gained it for ever."

Another who had cause for concern was Robert de Bruce. To pile pressure on Edward, Philip dangled the threat of John Balliol’s return to Scotland. If this happened, it could spell the end of Bruce’s ambitions as well as Edward’s. As the English and French diplomats cut and parried at each other in Glasgow, Brucie had much to ponder.

|

| Philip le Bel |

The terms discussed expose the weakness of Edward’s position in Scotland at this time. His envoys agreed to a truce with the Scots, to commence on 26 January 1302 and end on 1 November. For the duration of the truce all of the lands and castles which he had taken in southwest Scotland during the summer of 1301 would be placed in the custody of Philip’s agents. When the truce expired, they would be handed back to the English. The Scots, apparently, didn’t get a look-in.

Edward had been burned like this before. In the negotiations over Gascony in 1294, he had agreed to hand over key towns and castles to Philip, who would then return them after a grace period of forty days. Instead the French king simply broke his own covenant and confiscated the duchy.

Now it was happening all over again. Except it wasn’t. Edward wouldn’t fall for the same trick twice, and in the autumn of 1301 drew up new indentures for the supply of his garrisons in southwest Scotland. Massive purveyances of food were ordered from England and Ireland for the garrisons of Dumfries, Lochmaben and Ayr. This would not have happened if the English king meant to hand over his recent conquests to the French. Thus the peace talks at Glasgow were so much hot air: if Philip wanted those castles, he would have to send a French army to Scotland to take them.

|

| Robert de Bruce |

"Wherefore I counsel you forthwith to send great persons into Scotland; for if you can enter therein, you will have gained it for ever."

Another who had cause for concern was Robert de Bruce. To pile pressure on Edward, Philip dangled the threat of John Balliol’s return to Scotland. If this happened, it could spell the end of Bruce’s ambitions as well as Edward’s. As the English and French diplomats cut and parried at each other in Glasgow, Brucie had much to ponder.

Saturday, 9 November 2019

Guardians at the gates

In early September 1301, at about the same time as King Edward marched against Bothwell, the Guardians headed to the south-west to attack the English garrison at Lochmaben.

Possession of Lochmaben was of great strategic value to both sides. The port of Annan was only a short journey from the castle and the garrison could, like the one at Caerlaverock, be resupplied from the port at Skinburness. It also lay across an important road junction, controlling routes into Annandale and Nithsdale. This meant that the garrison at Lochmaben controlled access to Caerlaverock and Dumfries.

Back in September 1298, Edward captured Lochmaben after his victory at Falkirk and gave it to Sir Robert Clifford. It had previously been held by the Bruces, who for some reason chose not to build a stone castle on this important site. Instead Lochmaben was a timber fortification or ‘manerium’, and Clifford was tasked with strengthening it. Excavations in 1968 discovered evidence of a gateway and a palisade trench, dating from 1300 or thereabouts. Thus it would appear Clifford built an extra timber defence or pele, along with a large ditch to make approach from the landward side virtually impossible. Lochmaben was otherwise surrounded by water on three sides.

By autumn 1301 the English constable of Lochmaben was Sir Robert Tilliol. He had about 100 men in garrison, and was required to hold his wooden outpost against the combined strength of the Scottish field army. In early September he sent an urgent letter to the king, reporting that the Guardians were converging on him from the north and north-west. One part of the Scottish host, under Sir John Soules and the Earl of Buchan was camped at Loudon; the other was at Stonehouse near Strathaven under Simon Fraser, Sir Alexander Abernethy and Sir Herbert Morham.

Tilliol begged the king for reinforcements: 100 decent cavalry, led by a ‘good chieftain’, would do the trick. And he needed them in the next twenty-four hours. It is doubtful that his letter reached Edward in time - soon after Tilliol’s galloper went tearing up to Bothwell with his despatch, the Guardians were at the gates.

|

| Lochmaben |

Possession of Lochmaben was of great strategic value to both sides. The port of Annan was only a short journey from the castle and the garrison could, like the one at Caerlaverock, be resupplied from the port at Skinburness. It also lay across an important road junction, controlling routes into Annandale and Nithsdale. This meant that the garrison at Lochmaben controlled access to Caerlaverock and Dumfries.

Back in September 1298, Edward captured Lochmaben after his victory at Falkirk and gave it to Sir Robert Clifford. It had previously been held by the Bruces, who for some reason chose not to build a stone castle on this important site. Instead Lochmaben was a timber fortification or ‘manerium’, and Clifford was tasked with strengthening it. Excavations in 1968 discovered evidence of a gateway and a palisade trench, dating from 1300 or thereabouts. Thus it would appear Clifford built an extra timber defence or pele, along with a large ditch to make approach from the landward side virtually impossible. Lochmaben was otherwise surrounded by water on three sides.

By autumn 1301 the English constable of Lochmaben was Sir Robert Tilliol. He had about 100 men in garrison, and was required to hold his wooden outpost against the combined strength of the Scottish field army. In early September he sent an urgent letter to the king, reporting that the Guardians were converging on him from the north and north-west. One part of the Scottish host, under Sir John Soules and the Earl of Buchan was camped at Loudon; the other was at Stonehouse near Strathaven under Simon Fraser, Sir Alexander Abernethy and Sir Herbert Morham.

Tilliol begged the king for reinforcements: 100 decent cavalry, led by a ‘good chieftain’, would do the trick. And he needed them in the next twenty-four hours. It is doubtful that his letter reached Edward in time - soon after Tilliol’s galloper went tearing up to Bothwell with his despatch, the Guardians were at the gates.

Friday, 8 November 2019

The road to Bothwell

In early September 1301 the war in Scotland shifted up a gear. King Edward left Glasgow on the 4 and arrived the next day outside the walls of Bothwell Castle, on the banks of the Clyde a few miles to the southeast.

Bothwell was the property of Walter of Moravia, or Walter of Moray, known as Walter ‘the Rich’ for reasons that were presumably obvious. Many of his kinsmen had been captured at the battle of Dunbar in 1296, including his younger brother Andrew, who died in the Tower in April 1298. His nephew Andrew earned fame as the chap who, along with Sir William Wallace, defeated the Earl of Surrey at Stirling Bridge in 1297. Andrew shortly afterwards died of his wounds.

The castle appears to have changed hands three times in five years, and by September 1301 was back in Scottish possession. William the Rich had died the previous year, and his nearest heir was the three-year old Andrew, son of the late Guardian. Edward seems to have identified the Morays as a specific threat, and took personal charge of the operations at Bothwell. This was part of his laborious step-by-step reconquest of Scotland; the Scots were never going to fold again as they did in 1296, so the thing had to be done piecemeal, one castle and chunk of territory at a time.

Prior to the siege, on 10 August, Edward granted the barony of Bothwell, including castle and lands to the value of £1000, to Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke and John Comyn’s brother-in-law. At this stage the castle itself probably consisted of the main donjon tower, the prison tower, and the short connecting wall. The foundations of the remainder would have been protected by a timber palisade.

The siege lasted from 5-22 September. While it was in progress a siege tower or ‘belfry’ was constructed at Glasgow and hauled seven miles along a corduroy road to the castle; this was a log road or timber trackway made by placing logs perpendicular to the direction of the road. It was a rough mode of transport, and a danger to horses due to shifting loose logs, but an improvement on impassable mud or dirt roads. On 6 September, mindful of desertions, Edward paid out wages to his 6800 infantry.

Whatever his failings elsewhere, the king was a dab hand at siegecraft. Possibly he inherited this trait from grandpa John, who also loved a siege. The Guardians made no attempt to rescue Bothwell, and by 22 September the garrison had surrendered.

Bothwell was the property of Walter of Moravia, or Walter of Moray, known as Walter ‘the Rich’ for reasons that were presumably obvious. Many of his kinsmen had been captured at the battle of Dunbar in 1296, including his younger brother Andrew, who died in the Tower in April 1298. His nephew Andrew earned fame as the chap who, along with Sir William Wallace, defeated the Earl of Surrey at Stirling Bridge in 1297. Andrew shortly afterwards died of his wounds.

The castle appears to have changed hands three times in five years, and by September 1301 was back in Scottish possession. William the Rich had died the previous year, and his nearest heir was the three-year old Andrew, son of the late Guardian. Edward seems to have identified the Morays as a specific threat, and took personal charge of the operations at Bothwell. This was part of his laborious step-by-step reconquest of Scotland; the Scots were never going to fold again as they did in 1296, so the thing had to be done piecemeal, one castle and chunk of territory at a time.

Prior to the siege, on 10 August, Edward granted the barony of Bothwell, including castle and lands to the value of £1000, to Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke and John Comyn’s brother-in-law. At this stage the castle itself probably consisted of the main donjon tower, the prison tower, and the short connecting wall. The foundations of the remainder would have been protected by a timber palisade.

The siege lasted from 5-22 September. While it was in progress a siege tower or ‘belfry’ was constructed at Glasgow and hauled seven miles along a corduroy road to the castle; this was a log road or timber trackway made by placing logs perpendicular to the direction of the road. It was a rough mode of transport, and a danger to horses due to shifting loose logs, but an improvement on impassable mud or dirt roads. On 6 September, mindful of desertions, Edward paid out wages to his 6800 infantry.

Whatever his failings elsewhere, the king was a dab hand at siegecraft. Possibly he inherited this trait from grandpa John, who also loved a siege. The Guardians made no attempt to rescue Bothwell, and by 22 September the garrison had surrendered.

Thursday, 7 November 2019

Of alms and iron kings

August 1301. While his father trundled towards Glasgow, the Prince of Wales set about reducing Scottish castles in the west. He had already captured Ayr, and shortly afterwards seized Dalswinton. This was a Comyn castle - literally known as Comyn’s Castle - and lay six miles northwest of Dumfries. The castle was demolished in the late 18th century, though the ruin of a tower (pictured) stands on the site.

Prince Edward sent a tiny garrison of four men-at-arms, led by Sir John Botetourt, to hold Dalswinton. They were paid for their stay at the castle between 5-25 September. Botetourt was fresh from convalescence in Gascony, where he had been severely wounded defending two Franciscan brothers from the French. For centuries he was thought to be a bastard son of Edward I, until closer inspection revealed this was the result of some spilled ink on a genealogy roll. Perhaps bear that in mind, the next time someone claims to be the 27th great-great-grandson of Julius Caesar.

The prince marched on down the coast from Ayr to attack Robert de Bruce’s castle at Turnberry. Bruce was still fighting for the Scots at this point, even though the Guardians had sacked him the previous summer. To begin with, he may have watched events unfold with a certain detached amusement: his successor in office, Ingram d’Umfraville, had distinguished himself by running away from King Edward in Galloway.

Bruce would have been far less amused at the loss of Turnberry. The castle had fallen by 2 September when Edward senior, at Glasgow, received “good rumours” from his son. Sir Montasini de Novelliano, the Gascon knight recently installed as constable of Ayr, was gifted new robes at Turnberry on the same date. With an unusual touch of sensitivity, King Edward gave alms in thanks to Saint Kentigern, otherwise known as Mungo, the reputed founder and patron saint of Glasgow.

Some ghastly news - for Bruce and Edward both - then arrived from France. Over the summer, the papacy handed over custody of John Balliol to Philip le Bel, who allowed Balliol to reside in his ancestral of Bailleul in Picardy. Balliol might well have been kidnapped - just as Philip had previously kidnapped the daughter of Count Guy of Flanders - but the sequence of events is unclear.

Everyone now looked to Philip, to see which way the Iron King would jump. It was commonly believed that he would send Balliol to reclaim his throne in Scotland “with a great force” of French soldiers at his back. But Philip had a more subtle ploy in mind.

Prince Edward sent a tiny garrison of four men-at-arms, led by Sir John Botetourt, to hold Dalswinton. They were paid for their stay at the castle between 5-25 September. Botetourt was fresh from convalescence in Gascony, where he had been severely wounded defending two Franciscan brothers from the French. For centuries he was thought to be a bastard son of Edward I, until closer inspection revealed this was the result of some spilled ink on a genealogy roll. Perhaps bear that in mind, the next time someone claims to be the 27th great-great-grandson of Julius Caesar.

The prince marched on down the coast from Ayr to attack Robert de Bruce’s castle at Turnberry. Bruce was still fighting for the Scots at this point, even though the Guardians had sacked him the previous summer. To begin with, he may have watched events unfold with a certain detached amusement: his successor in office, Ingram d’Umfraville, had distinguished himself by running away from King Edward in Galloway.

Bruce would have been far less amused at the loss of Turnberry. The castle had fallen by 2 September when Edward senior, at Glasgow, received “good rumours” from his son. Sir Montasini de Novelliano, the Gascon knight recently installed as constable of Ayr, was gifted new robes at Turnberry on the same date. With an unusual touch of sensitivity, King Edward gave alms in thanks to Saint Kentigern, otherwise known as Mungo, the reputed founder and patron saint of Glasgow.

Some ghastly news - for Bruce and Edward both - then arrived from France. Over the summer, the papacy handed over custody of John Balliol to Philip le Bel, who allowed Balliol to reside in his ancestral of Bailleul in Picardy. Balliol might well have been kidnapped - just as Philip had previously kidnapped the daughter of Count Guy of Flanders - but the sequence of events is unclear.

Everyone now looked to Philip, to see which way the Iron King would jump. It was commonly believed that he would send Balliol to reclaim his throne in Scotland “with a great force” of French soldiers at his back. But Philip had a more subtle ploy in mind.

Wednesday, 6 November 2019

Gnarly old forwards

In late July 1301 Edward I led his army from Berwick and marched west through the borders, staying at Peebles for two weeks before pushing onto into Lanarkshire.

The Guardians had mustered their field army much further south, in the region of Lochmaben and Galloway. They seem to have kept a smaller force in Lanarkshire, sent to harass the English king’s army on his march towards Glasgow. On 28 July, the day on which Edward arrived at Peebles, one of his small squad of twenty crossbowmen was captured by the Scots. His name was Basculus - probably a Gascon - and the Scots took his bay horse, later valued at £12. It appears Basculus himself was released, since he later submitted the claim for compensation.

Edward slowly bulldozed his way through the central Lowlands, with the Scots hanging off him like a bunch of determined backs off a gnarly old prop forward. Unlike the Anglo-Celtic smorgasbord of his son’s army in the west, the majority of his men were English. In contrast to the previous summer in Galloway, they didn’t desert in large numbers. Or at least not at first: the number of 6800 infantry remained fairly consistent throughout July and August, and only started to drop off in September.

The king arrived at Glasgow on 21 August. Shortly after this date, while still at Glasgow, Edward sent men to garrison the castles of Carstairs and Kirkintilloch. These had probably been left empty, but now he wanted to strengthen his hold on southern Scotland. He appointed Sir Walter Burghdon, a Scot who held lands in Roxburghshire, as keeper of Carstairs.

Burghdon had the following men in garrison:

30 men-at-arms

2 knights

80 archers

A daily rate of pay for these men was calculated at £2 6 shillings. Kirkintilloch had been a private castle in the hands of John Comyn of Badenoch until 1296. At some point between 1296-1301 Edward granted it to Hugh Despenser, who showed little interest in the place. In the autumn of 1301 Sir William Francis was installed there with:

27 men-at-arms

2 smiths

1 nightwatchman

1 artillery maker

19 crossbowmen

20 archers

The Guardians had mustered their field army much further south, in the region of Lochmaben and Galloway. They seem to have kept a smaller force in Lanarkshire, sent to harass the English king’s army on his march towards Glasgow. On 28 July, the day on which Edward arrived at Peebles, one of his small squad of twenty crossbowmen was captured by the Scots. His name was Basculus - probably a Gascon - and the Scots took his bay horse, later valued at £12. It appears Basculus himself was released, since he later submitted the claim for compensation.

Edward slowly bulldozed his way through the central Lowlands, with the Scots hanging off him like a bunch of determined backs off a gnarly old prop forward. Unlike the Anglo-Celtic smorgasbord of his son’s army in the west, the majority of his men were English. In contrast to the previous summer in Galloway, they didn’t desert in large numbers. Or at least not at first: the number of 6800 infantry remained fairly consistent throughout July and August, and only started to drop off in September.

The king arrived at Glasgow on 21 August. Shortly after this date, while still at Glasgow, Edward sent men to garrison the castles of Carstairs and Kirkintilloch. These had probably been left empty, but now he wanted to strengthen his hold on southern Scotland. He appointed Sir Walter Burghdon, a Scot who held lands in Roxburghshire, as keeper of Carstairs.

Burghdon had the following men in garrison:

30 men-at-arms

2 knights

80 archers

A daily rate of pay for these men was calculated at £2 6 shillings. Kirkintilloch had been a private castle in the hands of John Comyn of Badenoch until 1296. At some point between 1296-1301 Edward granted it to Hugh Despenser, who showed little interest in the place. In the autumn of 1301 Sir William Francis was installed there with:

27 men-at-arms

2 smiths

1 nightwatchman

1 artillery maker

19 crossbowmen

20 archers

Cilmeri: another slant

Below is the well-known entry from the Brut describing the last days of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd:

“And then was effected the betrayal of Llywelyn in the belfry of Bangor by his own men. And then Llywelyn ap Gruffudd left Dafydd, his brother, guarding Gwynedd, and he himself and his host went to gain possession of Powys and Buellt. And he gained possession of them as far as Llanganten. And thereupon he sent his men and his steward to receive the homage of the men of Brycheiniog, and the prince was left with but a few men with him.”